Mistress of the House

Evelyn Wallace knew exactly what she wanted from her life. Along the way, things didn’t go quite as planned.

If there’s one word that describes Evelyn Wallace, it’s persistent. Through hardship, betrayal, and being a single mother, she never gave up. Why, you may ask? It was love–unconditional and unwavering. And it lasted her entire life. But as you’ll see, the road she traveled was lengthy and twisted.

***

In the summer of 1847, when Evelyn was 17, she and her family attended what would become a fateful church revival meeting in central Tennessee, where they lived. At that time, it was very rural, with a sparse population and few churches. So church revival meetings were pretty much the only opportunity for settlers to attend church services. Like most people, Evelyn’s family had traveled to be there (although not as far as many attendees had), and they’d set up camp for the four days the meeting would be happening.

Let’s be clear, though, this was not the kind of revival meeting (or tent revival) that came into being in the 1900’s. There was still a religious aspect, to be sure, but these meetings were in equal part social events that included providing a way for people to look for things like marriage partners, especially young people…

Lincoln County, TN; photo: landwatch.com

***

Because they were camping, all of the cooking was done outside over open fires. This is where we find Evelyn after the morning service of the first day of the revival meeting. Her Ma was getting annoyed. Or Evelyn thought that was the case because she’d almost tipped a pot of beans into the cooking fire.

“Oh for heaven’s sake! Go talk to the boy!” Ma said, doing her best to hide her smile.

Evelyn, for her part, tried to deny (with no success) that she was distracted by James Waite, the handsome young man who’d introduced himself and his two brothers, Bennett and Roger, just before the morning service. (They’d sat in the chairs in front of Evelyn and her family.) The three brothers, now standing together a short way away, were also encamped nearby, but they’d come from their home in Illinois to settle some family business matters, not specifically to attend the revival meeting.

Ma shooed her away, and Evelyn, blushing furiously, didn’t argue. She started to sidle her way toward James but hesitated. Maybe he was just being polite when he’d introduced himself. Then again, she thought he might’ve been flirting too.

Over the last couple of years, the socializing that was part of the revival meetings had taken on a different tone. It was no longer just catching up with friends and family who lived far away. Now it was also meeting potential husbands and wives (although Evelyn didn’t quite recognize it as such).

James saw her and excused himself from his brothers. He came over to talk to her, which made her blush even harder. She wanted to flee in a cloud of embarrassment, but before she could, he was standing right there talking to her.

“We won’t be here too long,” he said. “We came to sell off some land our grandfather owned. He died a few months ago.”

“Oh, I’m sorry,” Evelyn said.

“Thanks,” James murmured and looked away.

“Miss Wallace,” he said looking back awkwardly. “I’d be mightily pleased if you’d let me sit with you at the evening service.”

Evelyn, despite never having been to the ocean, could swear she heard it roaring in her ears. So, unable to find her voice, she just nodded…and blushed… and returned a slightly self-conscious smile.

Bennett and Roger, for their part, exchanged a knowing look when James told them he wouldn’t be sitting with them at the evening service.

***

To no one’s surprise, it was just six months later Evelyn excitedly announced that James had proposed and she intended to accept. Her Ma and Pa, on the other hand, were not quite as joyful. They wanted Evelyn to wait until she was 18 to get married. One thing they couldn’t deny, however, was that James certainly appeared to be serious. When his brothers returned to Illinois, James had stayed on to court Evelyn properly.

Even so, to Evelyn’s rather pointed frustration, it seemed that her Ma and Pa were incapable of accepting why they couldn’t wait the few months until Evelyn’s 18th birthday. When they repeated their demand for information, she had to exert considerable control to keep from snapping at them.

“Once again,” she said after taking a deep breath, “because James and his brothers are going to enlist in the Army to fight in the Mexican War.” (Which had been raging for almost a year at that point.) “He’s staying on here long enough for the wedding,” she went on, “and he’ll get us to his homestead in Arkansas, but he’s anxious to enlist,” she said, thinking that would be the end of it. But it wasn’t.

Ma gave her a dubious look but didn’t articulate what she suspected. Pa’s mind, on the other hand, went to a different matter. He pointed out, again, that the land James had was at least two weeks away (going from central Tennessee to central Arkansas). They were worried about her moving so far away, and although she would never admit it to them, Evelyn agreed. The long journey, in addition to the thought of being so far from home, scared her. And to make her fears worse, the land was in territory that had recently been cleared of the Native tribes who’d lived there for ages. She’d heard stories about the attacks in Tennessee when the Cherokee had first been driven out (leading to what would later be known as the Trail of Tears).

What if there are Indian attacks in Arkansas? She wondered with a thrill of fear.

One comforting thought was that her sister in Texarkana and her brother in St. Louis would come help her settle into her new home. And there were Wallace cousins living not too far from the part of Arkansas she’d be moving to. So Evelyn did her best to quell Ma and Pa’s apprehension, as well as her own.

“It’s just as far away no matter how many months I wait. I love him and want to marry him before he goes to war,” she said emphatically. Concern remained etched in her parents' faces, so she gave them both a hug. “I’ll be fine,” she said. Ma and Pa didn’t look at all reassured but reluctantly agreed that they wouldn’t stop her.

***

The next two months brought the biggest changes in Evelyn’s young life, starting with her wedding. It was happy overall, but the knowledge that she would soon be leaving for a new, distant home lent an underlying air of melancholy that went unacknowledged even as her journey to Arkansas began the next morning.

It took a little more than two weeks to get to their farm, and on the way, Evelyn constantly marveled at how lush and green the scenery was. Once they arrived, it hadn’t taken long to set up housekeeping, but despite the captivating landscape, it didn’t really feel like home yet.

I suppose that will come with time, though, she thought as she stood at the door of their little house, watching the sunrise.

The hills that surrounded their property were brightening and shifting from black to green as the sun came up. This was usually calming, but not today. She couldn’t fight down a feeling of dread knowing that James would be leaving that morning for Alton, Illinois to enlist. He’d arranged to meet up with Bennett and Roger there, and after they signed up, they’d start three months of training. What really worried her, however, was that after basic training, they’d be sent to fight in Mexico.

Washington County, AR; photo: TripAdvisor

She was struggling to hold back tears when he came to the door with his pack. He kissed her and promised to come back, then gently pressed his hand against her belly. She had told him the day before that she was expecting, knowing he probably wouldn’t be there when the baby was born.

“Now don’t fret,” he said. “Your brother should be here tonight, and your sister won’t be far behind.”

She nodded, and unable to speak, watched and waved until she couldn’t see him any longer. She lingered in the doorway for a while after that, hoping against hope he’d turn around and come back. But she knew that was foolish. For the first time since they’d met, she felt much too young for everything that was happening. She reminded herself that Ma had taught her everything she needed to know to run a household, and in addition to her brother and sister, her cousin Levi had sent his oldest son, Levi Junior, to stay with her and help out with chores. So she wasn’t alone.

“But none of them are James,” she said to herself with a sigh.

The sun was fully up now, so she shook off her dreary thoughts, smoothed her skirt, and cast one more longing glance up the road James had taken.

***

Not long after he’d left, Evelyn started getting letters from James. The first one described getting to the induction and training camp in Alton, and letters continued to arrive every week or two (mail service being what it was back in the mid-19th century). They didn’t stop even when James had been in combat. He wanted to be supportive during her pregnancy even though he was fighting in the war. In all of this correspondence, they made decisions about things like what the baby’s name would be: Mason, if it was a boy, and Madeleine, if it was a girl. Evelyn treasured every letter, not just because she wanted him to be involved in these kinds of choices, but also, perhaps more importantly, because it was reassurance he was still alive. Even so, it wasn’t until Mason (yes, she gave birth to a boy) was six months old that she finally got the letter she’d been hoping for. She read it, then re-read it, and then, for good measure, read it a third time, partly to help the news to sink in and partly because Mason wouldn’t stop fussing and wiggling.

“Daddy’s coming home!” she said, grinning like a fool while bouncing him. Mason, for his part, was impressively unimpressed and determined to continue fussing.

As happy as Evelyn was, the letter also contained bad news: James and his brothers had all contracted malaria. And while James and Roger were doing better, Bennett was very sick. But Evelyn didn’t have long to consider this as Mason started wail, apparently offended that he wasn’t getting her undivided attention. When he finally allowed himself to be mollified, Evelyn put him in his crib and turned to preparations for James’ homecoming.

***

As it turned out, however, James was forced to delay his return. Bennett continued to weaken and died as quickly as James and Roger regained their strength. All three brothers had prepared to lose each other in the war, but that didn’t help when dealing with the shock of losing Bennet to an illness rather than a bullet. Roger and James took care of sending Bennett’s body back to his home for burial, then made their goodbyes to head back to their own homes.

So James returned to Arkansas through a combination of walking and getting the occasional wagon ride from infrequent passersby. And Evelyn constantly kept an eye out until one day he appeared as a distant speck far up the dirt road that ran by their homestead. Soon, he was at the doorstep dropping his pack on the porch.

This, Evelyn thought, makes up for all the waiting.

She exclaimed in delight and jumped into James’ arms. After an extended period of hugging and kissing, she lifted Mason out of his crib and introduced him to his father. James took the baby and held him out to take a good look.

“Why, you’re a fine lookin’ young ‘un!” he said, marveling at his son.

Soon he sat down with Mason in his lap and an arm around Evelyn’s waist. She leaned into him, thinking about the long, happy years they had ahead, now that the hardest days were over. Little did she know, her not-too-distant self would find this sentiment to be overly optimistic.

***

And just a few days later, Evelyn did indeed realize (with more than a little chagrin) how naive she’d been. Mason was teething, and nothing would quiet him. And much worse, soon after getting home, James had come down with a fever and rash that Evelyn feared might be smallpox instead of a malaria relapse. So she had her hands full tending to him and keeping a close eye on Mason for any sign he might be sick too. Thankfully, Levi Jr. had come to help out again, which Evelyn told him repeatedly was a life-saver.

He just smiled shyly and said. “Glad I can help out family.”

After a couple of weeks, Evelyn started to relax. Mason remained healthy, especially his lungs (which he constantly demonstrated by wailing loudly), and James looked to be on the mend too. Then one morning, she woke up with a fever and rash like James had had. For some reason, though, it hit her harder, which she didn’t understand until she realized she was expecting again. She decided to wait until she was well before telling James, just to be sure that everything was fine. But that didn’t take long.

“Mustn’t shirk. Got to get up and get back to work,” she told herself as soon as she could get on her feet and do chores.

Before long her strength returned and brought with it her characteristic optimism.

1849 will be a good year, she thought.

***

But once again, her optimism came into tragic conflict with reality. Her prediction for 1849 didn’t work out. Her second pregnancy ended with a stillborn son. After that she’d sworn off making rosy predictions about the future, and it was just as well–it wasn’t even halfway through 1850 now, and she’d miscarried her third pregnancy.

She lay on her side, sobbing quietly while Martha, the local midwife, stopped cleaning up and went to pat Evelyn’s hand.

“There, there, love,” she said in her thick Irish accent.

Evelyn tried to regain her composure, but despite Martha’s kindness, she felt guilty and completely alone. She and James both wanted a big family, but after two failed pregnancies, she was worried that she wouldn’t be able to give James more than their one child. This thought alone broke her heart, but when the very real possibility that Mason might end up being an only child occurred to her, her misery felt unbearable.

Martha pulled the blanket over her and said, “Now you get some rest, dearie.”

Evelyn could hear her sister, Isabel, cajoling Mason to eat, but he was upset by the sounds coming from the bedroom, and wanted to come see her to get comfort and reassurance. That wouldn’t be good for him, however, so she pulled herself into a ball and wished that James was there.

But he was far away. He’d had to rush off to Illinois when he got word that his stepmother had died suddenly, which left his father alone to take care of his farm and five children.

“I’m so sorry,”James had apologized, “but my Pa needs my help.”

So do I, Evelyn had thought, but kept that response in her head and instead said, ”I understand. He’s surely overwhelmed.”

At the time, it was easier not to feel resentful knowing that he planned on being back in time for the birth that now wouldn’t happen. But as usual, nothing had gone as expected.

***

Shortly after her miscarriage, Evelyn wrote to James to give him the sad news. She hoped the letter would reach Illinois after he’d left to come back home, but in James’ reply letter he wrote:

Pa’s already courting a new bride, and she’s just a little older than me.

Evelyn’s first reaction was shock, but then she realized it wasn’t all that surprising, maybe even a bit amusing.

James’ father was a small, unassuming man who’d been married three times at that point, and each time he remarried, his wives got progressively younger.

“He sure doesn’t let the grass grow under his feet… or on his wives’ graves,” she said out loud, but only Mason was there to hear her, and he just gave her a curious look.

Given the impending nuptials, Evelyn expected James to be reassured that his father would have someone to take care of his household and children. Consequently, she expected James to come home very soon. But oh those pesky expectations. Instead of James himself coming down the road, she got another letter where James told her he was staying in Illinois for the wedding.

She couldn’t decide whether she was more sad or furious. Without a doubt, she understood the importance of family, but she and Mason were his family too! How could James constantly put his father before them?

It was also hurtful that his letter was so brief and impersonal, but she didn’t have time to give it much thought. She wiped away angry tears and shoved the letter into her apron pocket. She’d answer it later–right now she had her own family to attend to.

***

In the following weeks, it was hard to overcome lingering resentment, but Evelyn managed to do so. And now, months later, all she could feel was joy as James slipped into the bedroom and sat down next to her on the bed. She handed him their daughter, and he ran a finger along her tiny cheek.

“Clementine?” he asked.

Evelyn nodded and let her grateful tears flow–she’d been terrified to even think about names, just in case, but James had convinced her to tell him what she’d chosen as the day got closer. She wiped her eyes, and marveled at her daughter ’s wrinkled little face as she yawned.

James caressed the tiny head and said, “Hello there,Clementine.”

*

Isabel hadn’t been able to come help with Evelyn’s fourth pregnancy, but cousin Levi seemed to have an endless supply of teenage children to share as helpers. His daughter Nancy was in the kitchen, washing Mason’s face and hands so he could meet his baby sister. James went out to join her and started on one of his long-winded jags, prattling on about the giant birds he saw one afternoon when he was in Illinois, and how they had tried to carry off one of their calves. Evelyn sighed and decided to rescue her from the story before it went on any longer. She called to Nancy and asked her to bring Mason in.

Recreation of the Piasa Thunderbird, first seen in the late 17th century by European explorers near Alton, IL; Photo: Burfalcy/Wiki Commons/CC BY SA 3.0

James had always been a fan of tall tales, and Evelyn had enjoyed listening to them. But it seemed that over the last few years, his stories had changed. He’d taken to telling her ominous stories about the Indians who had lived in the area, knowing that she was afraid of attacks and raids. And he’d become fixated on the skeleton of a giant human that one of their neighbors had claimed to find while digging a well. The skeleton got bigger every time James told the story, and he was convinced that they could sell it and become rich. She tried to dismiss the stories as just more of his tomfoolery, but they bothered her. It was almost as if he believed that his grandiose tales were true.

What bothered her the most, though, was that James’ behavior was a continuation (worsening, really) of strange patterns she’d observed over the past few years. He’d been making regular trips to Illinois to visit his family, and they were always months long.

They argued about those trips frequently, but it made no difference–James would be off on another visit to help his family, leaving Evelyn resentful and embarrassed. Her family and neighbors were ready to help while James was away. She gladly accepted the help, even though she noticed the looks that passed between people when she mentioned that James had gone again.

She was thankfully distracted from this line of thought when Nancy led Mason into the bedroom. The little boy’s eyes widened when he saw his new sister. Evelyn’s heart jumped at his reaction, and once again, any bitterness about James was swept away.

***

This routine on the part of James persisted, frustratingly for Evelyn, over the next few years, which she was pondering as she fanned herself trying to mitigate the Texas heat. It was March of 1865, and Evelyn was heavily pregnant again, the result of one of James’ infrequent trips home. It seemed to be going well, but for once, she wasn’t getting her hopes up.

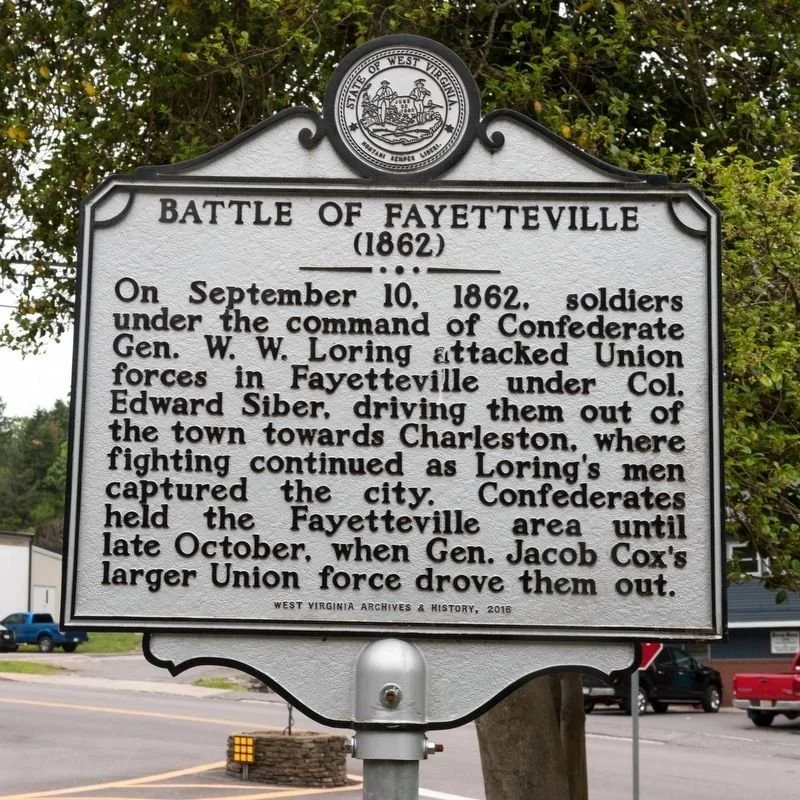

Battle of Fayetteville marker; photo: J.J. Prats, 2023

Her sister came into the room and announced “The Yankees took Fayetteville.”

Evelyn groaned and struggled out of her chair. Isabel put a hand on her back to steady her, then showed her the newspaper.

She was disturbed–their farm was only 40 miles from Fayetteville, and there had been a steady stream of Union and Confederate soldiers through the area. James had come back from Illinois and talked about his younger brother Amos joining the Union army. He looked haunted as he described seeing him off, and Evelyn knew James was remembering Bennett, who was just 20 when he died.

At first, Evelyn was happy to have James home. His presence made her feel safe. By autumn, though, she noticed that his erratic behavior had returned. He was telling his rambling stories again, most of them spiraling off into nonsense. He was ill, with fever and frequent relapses of the rash she’d seen before. When she tried to take care of him, he called her “Margaret,” and he was calling the children by the wrong names as well. Evelyn tried to tell herself that it was just delirium from the fever, but she was ashamed when she saw the contemptuous looks Mason cast at his father.

Once he was sufficiently recovered from his fever, James said that he had to go back to Illinois. This time, Evelyn hadn’t pressed him for an explanation. She closed the door behind him and went to write to her sister in Texarkana, asking to stay with her for the duration of the war.

*

Not long after that, her son Ewell was born, while the family–minus James–was living in Texarkana with her sister and her family. Mason joked quietly that he was relieved to finally have another boy in the house so that he wasn’t outnumbered anymore.

“Your sisters appreciate your patience,” Isabel told him, and he blushed and mumbled “Thank you kindly, ma’am”.

Isabel took Ewell from Evelyn and put him in his crib.

“Number six for you,” she said, and looked at her pointedly. Evelyn plucked at her dressing gown. She’d told Isabel everything, and was relieved and horrified that Isabel had come to the same conclusion as Evelyn–James had a second family in Illinois.

Isabel shooed the children out of the room and then turned back to Evelyn.

“Your husband is a lunatic,” she said. “You should see the letters he wrote to us.”

Evelyn nodded. She knew all too well.

“You’re better off without him,” Isabel went on, and again, Evelyn nodded in response. She had gone over everything in her mind countless times, and had finally come to a decision. After the war, she would go home and divorce James. She wasn’t sure she’d be able to prove that he was a bigamist, but there were enough people who’d attest to his insanity. She sighed as she settled back against the pillows. The thought of what was ahead exhausted her. She closed her eyes, and was asleep before Isabel slipped out of the room.

***

True to her decision, when the Civil War had drawn to a close, Evelyn returned to their farm in Arkansas with the full intention of divorcing James.

“Oh Mason,” Evelyn whispered as he guided the wagon past the ruins of farmhouses.

Nothing but chimneys, she thought.

The unfairness of it overwhelmed her. The people in their part of Arkansas hadn’t even wanted to secede, and here they were with nothing left. She dreaded seeing the remains of their home. She didn’t have any idea how they’d start over, or, more to the point, if they could.

As they approached their house, Mason gasped. “Ma?”

She squeezed Mason’s arm. They both saw. James was working to clear away the debris that was everywhere. He saw the wagon roll in and stopped to wave to them. Evelyn’s heart did a slow somersault–seeing him there next to the camp he’d set up reminded her of meeting him all those years ago. And like that day at the camp meeting, James held his hand out to her.

Illustration of Evelyn Wallace Waite

“Welcome home, Mrs Waite,” he said.

He leaned in to kiss her, but she pulled back. She handed Ewell to Mason and asked him to keep an eye on the other children. It was time to have a serious, likely unpleasant, conversation with James, who watched intently while she climbed down from the wagon and led him away. When they were out of earshot of their kids, Evelyn started, uninterested in beating around the bush.

“I know about your other family,” she said matter-of-factly. “Your other wife is Margaret, yes?”

James looked stricken but took a deep breath and answered, “Yes.”

Evelyn nodded. “And how many children?”

Again, James looked greatly embarrassed and uncomfortable, which actually pleased Evelyn.

“Six,” he finally answered. “But we lost two of them while they were just babies.” He looked down at his feet. “And there’s another one on the way.”

Evelyn closed her eyes and sighed. She’d prepared what she would say to James if he came back. She’d run through it in her head so many times that she could recite it almost without thinking.

“James, I’m not going to make this decision for you. You have to choose which family you want to be with. If it’s this one, you can’t ever go back to your other family. If it’s your other family, you have to go now and stay gone forever.”

She felt like a monster for suggesting that he abandon his pregnant second wife, but then she considered the number of times James had done exactly that to her.

James was still looking at his feet but said, “I want to be with you, Evvie. I want to rebuild our home.” Then he looked her squarely in the eyes.

“And what will happen to your other family?” she asked.

“My brothers will help Margaret. That’s what they’ve done all the other times I’ve been away.”

Evelyn realized she hated James a little bit.

Maybe even a bit more than that, she thought.

Even so, she couldn’t help but be glad he was going to stay with her and their children. She shivered, and he motioned for her to come sit by the fire he’d started. He hurried to get her some coffee, glancing over at her the whole time. He handed her the cup and she gave him a tiny smile and let her fingers brush over his when she took it. The look of relief on his face softened her hurt, angry heart.

I guess we’ll try, she thought without a tremendous feeling of optimism.

***

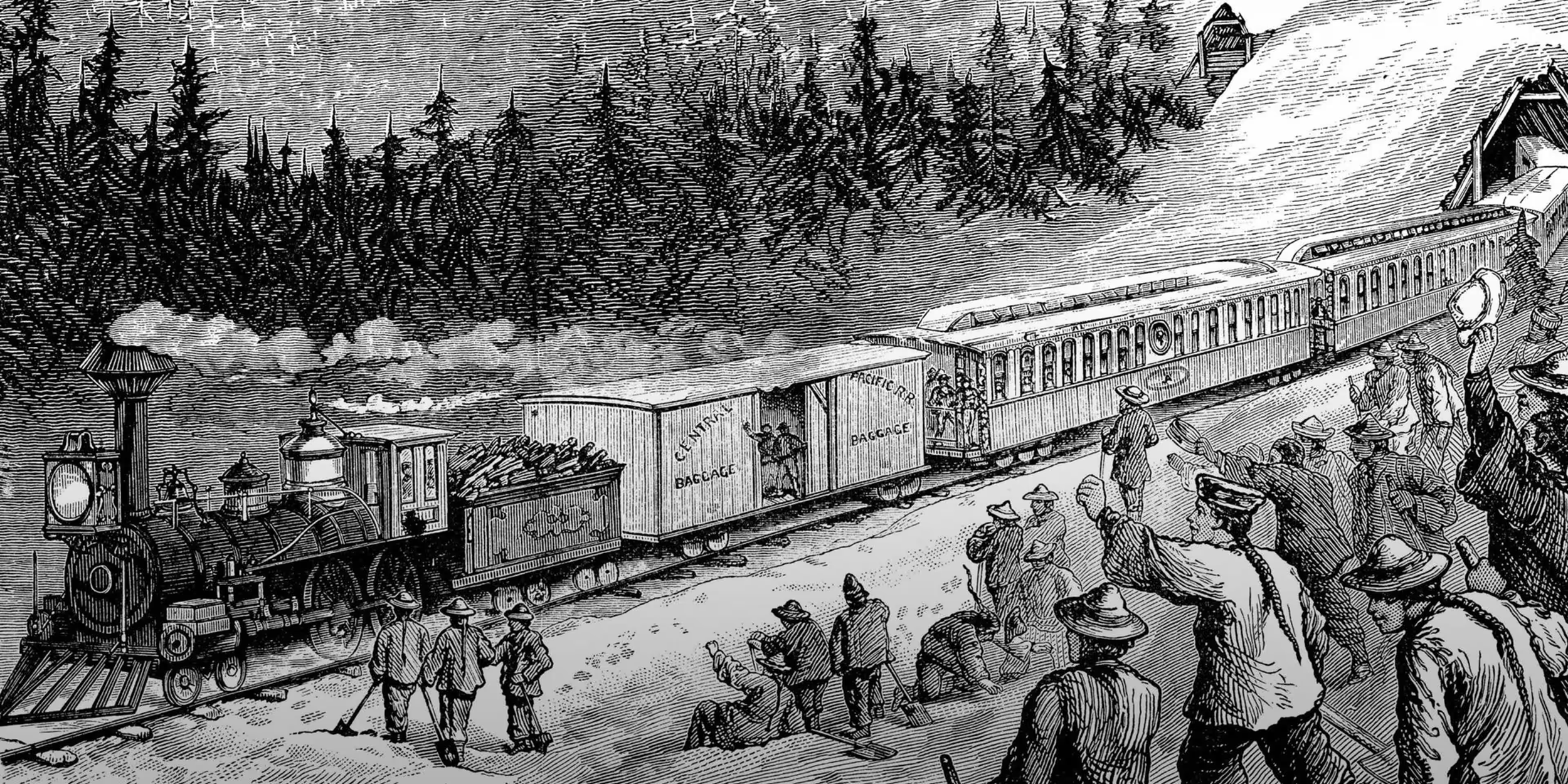

Evelyn recalled that conversation, and her misgivings, as she stood on the train platform. She and James and the children had worked incredibly hard trying to rebuild their farm, but to no avail.

Transcontinental railroad; image: The History Channel

It made her so sad her chest ached. She closed her eyes and remembered the way the sun looked coming up over the hills and the smell of pine.

A porter walked up to her and pointed to Mason who was standing at the end of the platform.

“Excuse me, ma’am,” he said. “That’s your husband over there, isn’t it?”

Evelyn shook her head. “No, that’s my son. I’m a widow.”

She had decided it was a lie she could live with.

The porter looked abashed and mumbled an apology. Mason spotted them and hurried to help with the trunks. Clementine and Vera looked after the younger children while Evelyn looked for the conductor. She knew moving to Oregon was the right decision, but at the moment it all felt overwhelming.

Soon, they were settled, with the exception of Mason, onto the benches that would serve as their seats. When Mason made his way back to them, he looked rumpled and sweaty from getting their trunks situated. He scooped up four-year-old Annie and put her on his lap, where she leaned against his chest. Evelyn watched, grateful to Mason for being more of a father to his siblings than their actual father had ever been. James had left for the last time two months before Annie’s birth, whereupon Mason, just 18 when she was born, had stepped in to help raise her.

“Ma, you’re telling people you’re a widow?”

Evelyn sat up straighter. Her head was throbbing and she didn’t want to talk about any of this.

“It’s easier, Mason,” she snapped. “A widow is respectable.”

“It’s nothing to be ashamed of,” he told her. “He’s the one who left.”

Evelyn gave him a look, and Mason dropped the conversation. He was 22 now, and knew better than to push his mother when she was done talking.

***

Baker County, OR; photo: landwatch.com

Although Evelyn had never let on to Mason, she’d been filled with doubt about the decision to leave Arkansas. Selling the land their farm had been on hadn’t brought in a lot of money, but it was enough to put them on a train to Oregon and to buy them a few acres in Baker County.

She sat on the porch of their farmhouse, resting after showing Annie how to make flapjacks. She closed her eyes and allowed herself to mull the turn her life had taken.

Despite her trepidation, she had to admit that the move had been good for the family. They’d been living on their new farm five years now, and it was flourishing under Mason’s guidance. She also knew that the younger children had adapted quickly and were happy here–it was the only home they remembered. Her older daughters had eventually settled in well, even though they’d needed a little more time. Clementine had married last year and was expecting her first child in the spring.

Evelyn hoped she would live to see her first grandchild. For a while she’d been able to dismiss her headaches and clumsiness as exhaustion from moving the family and rebuilding their life. But when her vision began to fade and she developed a noticeable tremor in her hands, she’d resigned herself to seeing a doctor. He’d diagnosed her with syphilis and given her mercury pills, along with a stern warning to live virtuously to avoid spreading her disease to anyone else.

She was humiliated, and furious that James had managed to let her down one last time. It had, of course, come from him–she’d been faithful to him her entire life.

It’s a secret that’ll die with me, she thought before pushing past that memory. No use lingering on something she couldn’t change.

Isabel had written to Evelyn three years ago, in 1872, with news that both James and his other wife were dead. There had been an outbreak of typhoid fever that had carried them both off and left six of their children orphaned. Evelyn felt tears welling in her eyes, behind her closed eyelids. The unfairness of it all struck her once again. She and the children, and even his other wife, had all deserved better from him.

Mason clumped up the porch steps, Ewell running behind him to wash up for breakfast. Evelyn quickly wiped her eyes. Mason paused before going inside.

“You all right, Ma?”

She looked up at him. She couldn’t make out his features in the shadows of the porch, just his silhouette. So like James he was, at least on the outside. She took great comfort, though, in the fact that on the inside, he was nothing like his father in all the best possible ways. She had to fight to hold back tears once again when Mason held out his hand to help her up.

“Let’s go have us some breakfast,” she said. “We’ll see how well Annie did with those flapjacks.”

***

Mason paused outside the telegraph office and soaked in the warmth of the late afternoon sun. He hoped this weather would hold. It was Ma’s favorite, and he liked the idea of burying her on such a fine day. He had just sent word to Isabel, letting her know that Ma had passed.

He was glad that she had lived to meet Inez, her first granddaughter. She seemed about to burst with pride, but had declined the offer to hold the baby–Evelyn had grown so weak that she was afraid of dropping her. She wasn’t too weak, though, to fix Clementine’s husband Thomas with a fierce look.

“You be a good man and take care of my daughter and grandbabies!”

Thomas seemed startled by the emphatic command, but he had assured her that he would be a good husband and father.

Evelyn died the following year, in 1877. Her family had been close by, but only Mason was in the room with her when she opened her eyes one last time. She asked him to find her wedding band and help her put it on. Mason did, even though he couldn’t understand.

“He was a different man the day he gave that to me,” was the only explanation she offered. “I’m very proud of you,” she said. “You’re a good man.”

“Thanks, Ma,” Mason whispered, finding it hard to maneuver words around the lump that had suddenly appeared in his throat.

Nothing more was said or needed. Mason held her hand until she drew her last breath.

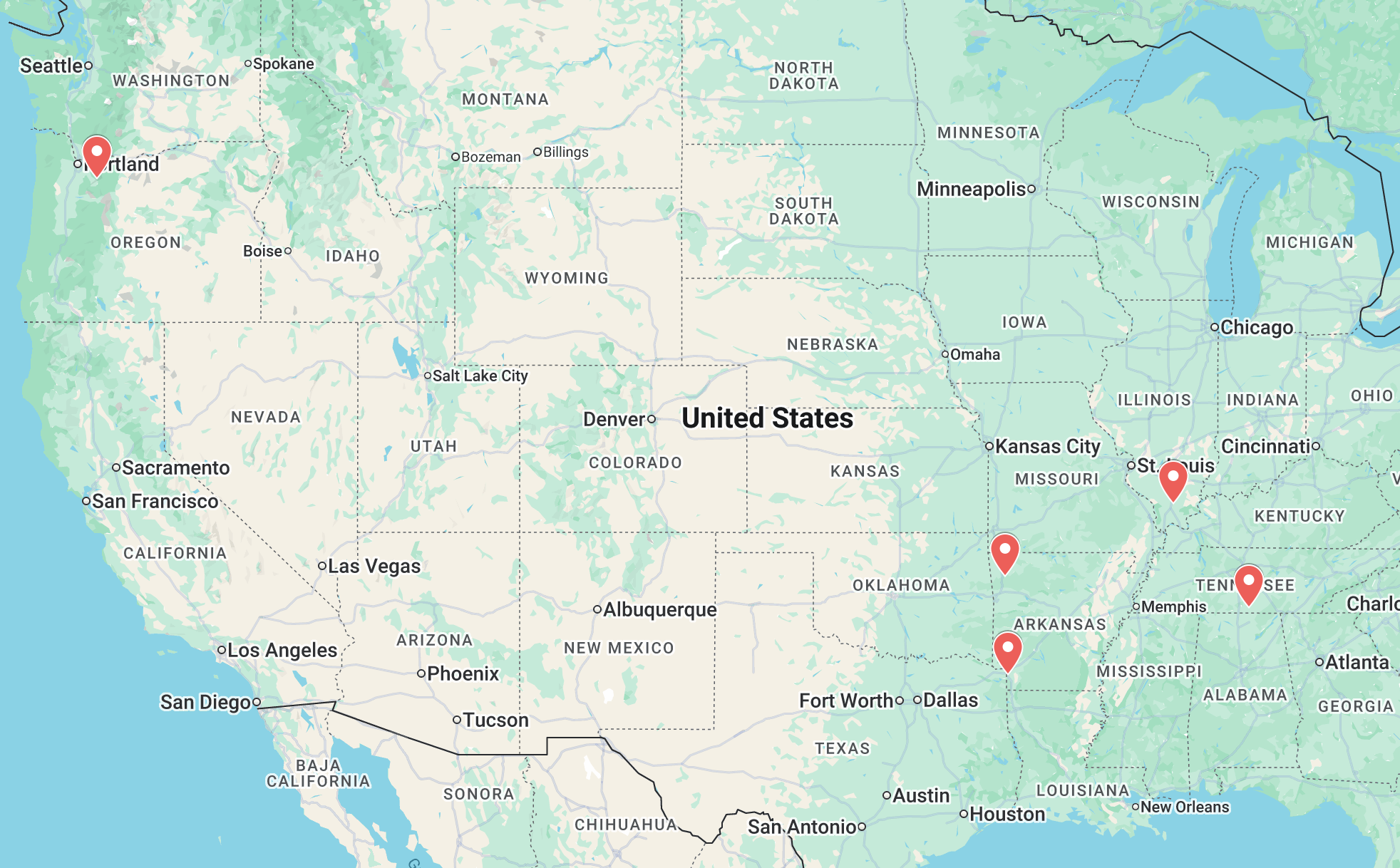

Location in the story. Top left: Baker County, Oregon; Center top: Washington County, Arkansas. Center bottom: Texarkana, Texas. Top right: Marion, Illinois. Bottom right: Lincoln County, Tennessee.

Learn more about the people, places, and events in this story by subscribing on Patreon.

The Silent Sisters

In the small town of Palmyra, Illinois, lived a family with two sisters who never spoke. Discover their world with this story.

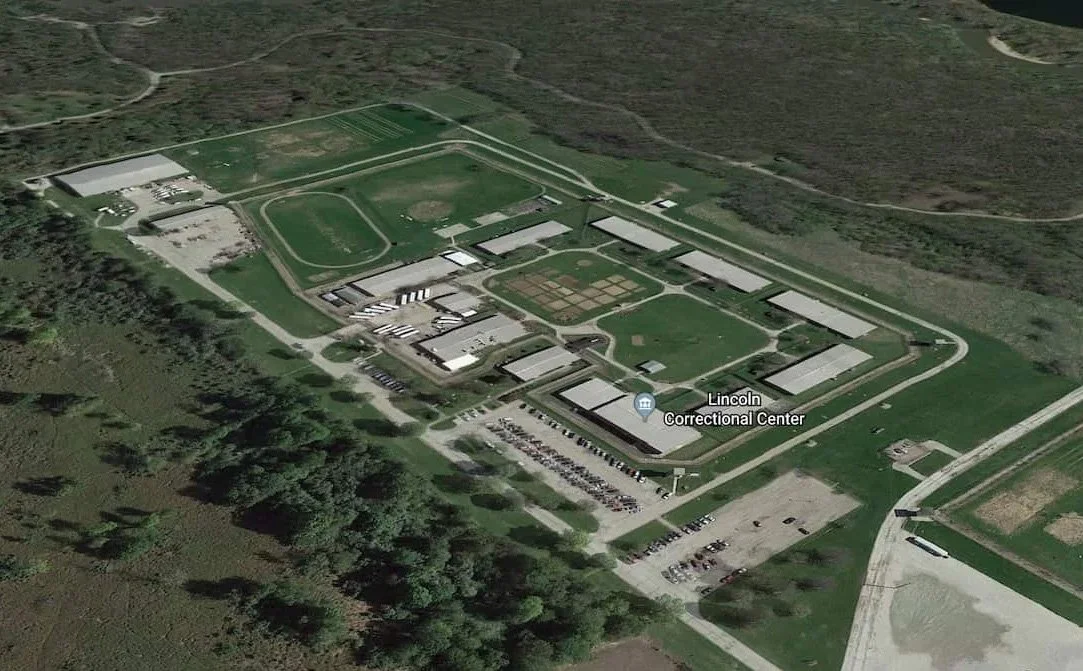

On the grounds of The Lincoln Correctional Center is a cemetery. This is normal for a prison. What is not normal is that several of the graves are for people who weren’t prisoners. One, in fact, is a shared grave for two sisters: Callie and Iona Sheppard. Who were they, and how did they come to be buried in a prison cemetery? The answer lies in this story.

Lincoln Correctional Center; photo: John Howard Association of Illinois

***

Cora was sniffling when she and her brother David walked in the door of their house in Palmyra, Illinois. As soon as Cora saw their mother, Eliza, she dropped her lunch pail and slate and ran to her, sobbing. Eliza was confused, but put an arm around her, and then turned a sharp eye and even sharper tongue on David.

“Young man, I told you to look after your sister! It was her first day of school, and here she is already upset!”

Hearing the commotion, their father, Cyrus, hurried in.

“Mama,” David said, “I don’t know why she’s crying. She didn’t say anything the whole walk home!”

Cyrus kneeled down in front of Cora and asked what was wrong. She wiped her eyes and with pauses for weepy choking, told him.

“Miss Clausen asked us all to tell something about ourselves, and I said I have a twin sister. At lunch, everyone teased me and said my sisters are stupid. I tried to tell them just because Callie and Iona don’t talk doesn’t mean they’re stupid. They just made fun of me even more!”

Eliza then scolded Cora (although not as sharply as David).

“You know you’re not supposed to talk about your sisters, young lady. Next time, you just ignore them.”

Cora started sobbing again, so Cyrus put his big hands around her upper arms and gave them a gentle squeeze.

“Cora, people don’t understand about Callie and Iona because they’re different. We protect them by not talking about them. Remember?”

Cora nodded, sniffling, and looked down at her feet.

“I know you love Callie, and you’re proud to be her twin. But if you hear anyone talking badly about your sisters, you need to pretend not to hear them. All right?”

Cora nodded again, and still sniffling, said, “Yessir.”

Cyrus gave her a brief hug and mussed her hair as he stood up. Eliza turned back to kneading her bread, and with an exasperated sigh, followed up.

“You don’t need to be telling people our business, girl. No one needs to know about your sisters.”

With all the noise and upset, no one had noticed Iona watching silently in the doorway. Callie had been with her initially but had run to hide as soon as she saw Cora crying. Iona followed Callie as soon as things seemed resolved, knowing she would need help calming down.

We don’t have any photos of the sisters. This illustration is an idea of what they may have looked like as children.

***

The Sheppard farm, where Cora, Callie, David, and Iona lived with their mother and father, was actually just outside of Palmyra. There had been just over 100 people living there in 1876 when Iona was born. When David was born two years later, the population had increased to half again as much. And two years after that, 1880, when Cora and Callie came along, there were 200 people living there. The growth continued to accelerate so much that every time Cora went into town with Papa, he’d lean over and tell her with a conspiratorial smile:

“Everyone must’ve heard about you and Callie and decided to move here.”

This made Cora giggle, but the trips into town were often upsetting too. Despite the family’s efforts to keep Callie and Iona hidden away, it seemed that everyone knew who they were. People would point and whisper. Cora tried to ignore them, but she heard bits and pieces like: “...so strange,” and “...such a shame,” and “...poor girls.” When she got mad, Papa would remind her to do her best to ignore it.

“People can be mean,” he said one time. “They probably don’t intend it that way, though.”

“So why do they say those things?” Cora asked.

“Well,” he said after a pause to think, “I do believe they get afraid of things they don’t understand.

It took some time for Cora to really understand this, but she eventually did. It even made a kind of unfair sense. Iona had lost her hearing when she’d gotten a bad infection in both ears when she was just two years old. Mama said she had started to talk when she got sick but had been mute since then. Instead, she communicated through pointing and gestures.

“Did Callie ever talk?” Cora had asked Mama once.

“No. She was always quiet, even when she was a baby.” Mama scowled a bit then. “People called her a changeling, said that she’d been swapped for a fairy child. So superstitious!” She turned to Cora and shook a finger. “I can tell you, though, I know my children, and Callie is still the same girl she always was.”

From an early age, Cora saw how Callie would withdraw when things got too loud or busy. Later, when she and David and Archie (who was two years younger than Cora and Callie) would play and tell each other stories, Callie would slip away to one of her hiding places, and Iona would follow her. Cora couldn’t remember a time when there wasn’t this close bond between the two girls.

Callie and Iona communicated with the improvised sign language Iona created, and all their siblings learned it too. (Eliza and Cyrus picked it up as well, though not as fluently.) Cora, however, worked at it harder than the others. She wanted to do more than just fetch them for chores and meals and baths. She desperately wanted to be part of Callie and Iona’s little circle.

***

Later, when Cora was 12, Cyrus had found her sitting on the porch, crying.

“I know what they’re saying, but I don’t understand so much of it!”

Her tears were partly from feeling left out, but more from frustration–she couldn’t really explain it, but it seemed to get harder all the time to talk with Callie and Iona. They seemed to be drifting further away from the rest of the family and closer to each other.

Papa sat down next to her and said, “I know, young ‘un. I wonder every day what goes on behind those blue eyes of theirs.”

He put an arm around Cora’s shoulders and gave her a quick squeeze.

“Their world isn’t quite connected to ours, I think. We just get to see a part of it.”

She nodded and felt a little better. It helped to know that Papa didn’t understand either.

***

A year later, 1893, started with great excitement. The World’s Fair was going to be in Chicago, and some of the families the Sheppards knew were going to make the trip. One of David’s friends had invited him to go with them and had generously extended the invitation to his brothers and sisters. Allen and Herb, the youngest brothers, weren’t old enough to go, but the rest of them were beside themselves with excitement that was destined to be short-lived.

“Absolutely not,” Mama said, leaving no room for discussion.

“But Mama…” David began.

“No!” she repeated, this time using her more steely tone. “Your father needs you boys helping him on the farm, and I need Cora’s help around the house.”

Cora knew Mama was expecting again and needed her help, especially since Callie and Iona couldn’t do much other than simple tasks. And it was true that Papa couldn’t manage without the boys, so there was no way any of them could go to the fair. It still hurt, however, and her eyes started to fill with tears.

David, knowing he’d get in worse trouble if he protested any further, meekly said, “Yes, Mama.”

Cora forced herself not to cry, knowing that Mama would yell at her if she did, maybe even give her a whooping. She also had to make sure she didn’t do anything that could be interpreted as pouting, so she saved it all for after she’d finished her chores and retreated to the room she shared with Callie and Iona. she sat on the bed with Iona next to her. Surprisingly, Callie sat on her other side. Usually she hid for at least a little while before coming out.

Cora patted herself on the chest–the way they expressed affection for each other–and Iona did the same. Callie watched them both, rubbing a frayed ribbon she wore on her dress to calm herself, and then she patted herself on the chest too.

***

As it turned out, going to the fair wouldn’t have worked out even if Mama had allowed it. A financial panic, followed by a depression, hit that spring. Papa planned to sell off part of the farm to make ends meet, and he and all the boys who were old enough to help were working hard to make the most of the corn crop before he did.

Later that fall, Eliza gave birth to a girl she named Sophie. It was a long, difficult labor, so Cora had a lot of extra work helping her mother take care of the new baby and basically run the household. She and David had quit school to take up extra work at home, so while Mama recuperated, Cora cared for Sophie; and David, when he wasn’t working in the fields, looked after Herb.

Cora was bouncing Sophie on her hip one morning while she worked on cleaning up from breakfast. It was a juggling act she feared she was losing when she noticed Iona had appeared by her side. She pointed to Sophie, made a cradling motion with her arms, and pointed to herself. Cora was stunned–Iona had never seemed interested or able to care for any of the younger children. It was good to have the help, though, so she signed for Iona to sit down and then carefully settled the baby in her arms. Iona patted herself on the chest while Sophie stared up at her as only babies can do. It was heartwarming to see, but Cora still kept a watchful eye on her sisters.

And sure enough, Sophie soon began crying. She was hungry yet again. Cora prepared a bottle (something she’d gotten used to doing on a very regular basis). About that time, Iona started getting fidgety, so Cora scooped up the baby and went back to bouncing her so Iona could go find Callie.

When Sophie finished her bottle and was back in her crib, Cora went to look for Callie and Iona. They were, as was often the case, sitting on the floor of their room playing one of their invented, incomprehensible games.

***

Life went on much like this for the next two years. Eliza recuperated and relied less on Cora for help, but she and David didn’t go back to school. She’d never liked it and was sure she’d learned everything she needed already–she could read, write, and do her numbers. The rest of the important things she was learning from Mama.

But while Sophie was growing to be a healthy toddler, Herb started to become listless. He wasn’t eating much, and he cried multiple times every day about tummy aches. He had just turned four, but he was so small, thin, and pale that he looked younger. The doctor started coming more often, leaving behind medicines that Herb would throw fits over taking. During one of these visits, the doctor noticed how Callie would sign with Iona, then run and hide. Cora overheard him talking to Mama one time, telling her about a school in Lincoln where they could send Iona and Callie.

“They’re going to become more of a burden to you and Cyrus as you get older, you know,” the doctor told her. “The Lincoln School will take care of them, teach them a trade, and maybe even treat their problems.”

After he left, Cora asked, “You won’t send Callie and Iona away, will you Mama?”

Eliza didn’t say anything immediately but finally shook her head.

“No,” she said quietly. “We’d never do that, girl.”

This reassured Cora, but she was still worried about Herb. He kept getting sicker and sadly died in the fall of 1895. Cora stayed home with Callie and Iona when the rest of the family went to his funeral. She doubted if they understood what had happened and didn’t know how to explain it. She didn’t even know if they could understand the concept of death. She found them standing in the door to the boys’ bedroom and tried to indicate that Herb was gone. Callie seemed scared and confused, but Iona was simply blank. They went back to their room and stayed there until the rest of the family came home.

***

Over the next five years, which included the turn of the century, there were more big changes in the Sheppard household. David had planned on marrying his sweetheart, a girl named Tillie, in the summer of 1900, but months before, one of their horses kicked him in the head. He lingered for a few days, but never woke up. He died on February 1st.

Cora was shocked. Of all her siblings, she had been closest to David, and he was the one who best understood how difficult the relationship with Iona and Callie could be. At the funeral, Cora clung to her fiancee, Oliver Barlow, whose father ran the Palmyra grocery store.

They put off their own wedding for a month out of respect, but the time passed quickly, and soon Callie and Iona were watching Cora pack her trunk. Once again, Cora wondered if they could understand what was happening. After the wedding, she’d be living in Palmyra, which was close by. So she’d be coming around often to visit and help, but still and all, it would be a significant adjustment for her sisters.

Palmyra in 1912; photo: History of Palmyra, IL Facebook group

***

The years following Cora and Oliver’s wedding brought first a son, Daniel, and then a daughter, Elsie.

“Aunt Sophie, I brought you a present!” exclaimed Daniel excitedly as he burst through the door.

As she’d intended when she got married, Cora went home weekly to visit and help out. Oliver and their children almost always came along. Their third child was due in just a month, so the amount she could help was limited. Despite that, it was good to just visit. And Daniel, who adored Sophie, wouldn’t miss a chance to come see her. He proudly handed Sophie an arrowhead he had found while digging around in the yard outside their house.

“Some Indians attacked us and I fought them off and kept one of their arrows!”

Oliver set Elsie down and said sternly, “Young man, don’t you fib to your aunt!”

Sophie took the arrowhead and gave her nephew a hug before he could start crying.

“Thank you, Daniel. Why don’t you go say hi to Grandma and Grandad.”

Cora gave her sister a grateful smile and went to find Iona and Callie. As she expected, they were in their room. Callie was in her usual hiding spot between the bed and the wall, trying to avoid the noise of two boisterous children and Oliver’s booming voice. Iona sat on the bed next to her. Cora joined them, and before long, Callie crept cautiously out of her hiding place and sat on the bed next to them. Callie had been fascinated by Cora’s belly with each of her pregnancies and loved to feel its roundness. Cora couldn’t spend as much time with her family as she would have liked, and it would soon be even less, so she appreciated moments like these.

After a few minutes, Elsie started crying, which sent Callie back to her hiding place. Iona looked confused, but stayed where she was. Cora worked her way off the bed so she could go see what the crisis was.

After soothing Elsie, she settled her and Daniel at the table with a snack and went to look for Sophie. In doing so, she overheard Oliver and her parents talking about a law that had just been passed in Illinois that allowed people to commit family members to asylums even if they weren’t insane. They were keeping their voices low, but Cora still caught parts of their discussion–enough to hear that they were considering sending Callie and Iona to the Lincoln School.

She waited until they were back home and the children were in bed before saying anything.

“How could you talk to my parents about committing my sisters without talking to me first?” she asked, not bothering to hide her anger. “And how could you even think of such a horrible thing?”

“We didn’t make any plans!” Oliver protested. “We were just talking about the future. You know as well as I do, Cora, they’re not going to be able to take care of Callie and Iona forever. Eventually they’ll need to go somewhere.”

“Then they’ll come here!”

Now it was Oliver’s turn to be angry. “We’ve never talked about that!”

Cora gestured to quiet down and pointed to the ceiling. “Don’t wake the children,” she said, keeping her voice low. “Anyway, now we’ve talked about it. I would rather take care of them here than send them to some asylum. I know how to take care of them–I’ve been doing it my entire life. When the time comes, we’ll make room for them.”

Oliver sighed. He knew it was pointless to argue, and besides, he didn’t want to burden Cora with his worries. He knew the US was going to end up joining the war in Europe and that he could be drafted. If he was, what would happen to his family? There was no way they could manage with two more people in their small house, especially two people who couldn’t help with chores much. Cora was staring at him, clearly holding back tears. He went to her and pulled her into a hug.

“All right. We’ll make room.”

***

Luckily, the question of what to do about Callie and Iona didn’t come up again until 1926 when things began to change dramatically. It started with a phone call from Archie early one morning. Mama had died.

“Papa said she had been having bad headaches, but she insisted that it was nothing to worry about,” Archie said. “Then he came in from chores last night and found her slumped over in her chair. The doctor thinks she had a stroke.”

Cora hurried home. When she got there, Papa was preparing the parlor for the wake. She noticed for the first time how old he looked. She remembered with a start that he was 83, and this was surely the worst of all the losses he’d endured. Cora went to help him move the furniture to make room for the casket Oliver and Daniel were hurriedly building. Cyrus stopped and squeezed her hand when he saw her.

“Sophie and Eula are getting your mother ready,” he said. He scowled a bit. He wasn’t fond of Archie’s wife.

Cora patted his hand. “Go sit down, Papa,” she said. “I can get the room ready.” She tried to be gentle but had to yell since he didn’t hear well anymore.

He nodded and eased himself into a chair in the quietest corner he could find, which actually was quiet only in comparison with the rest of the house. In a way, this made Cora glad because despite the commotion, Papa had the comfort of his children and grandchildren around him. What did worry her was that so much hustle and bustle would undoubtedly be upsetting for Callie and Iona. But she didn’t have time to worry about them at the moment. There were all kinds of preparations – the wake would happen tonight and the funeral would be tomorrow afternoon. Cora was extremely thankful for all the help from family.

She went about her business and finally looked at the clock when twilight started to fall. The wake would start soon, and she still needed to see if she could coax Callie and Iona to come down. She was sure it would be better for them to say goodbye to Mama tonight.

Cora found them in their room, as usual, and was able to entice Callie to join her and Iona on the bed. She waited a short time, then signed that they should go see Papa. She was relieved that they both stood up and followed her to the parlor. They hung back when they saw how the room had been changed, and Cora worried that Callie would run and hide again. She lingered in the doorway, rubbing the piece of ribbon on her dress. She looked ready to bolt but thankfully didn’t.

Cyrus took Iona’s hand and led her gently to the casket.

He signed “Mama goodbye” to her and waited. Iona studied his face, then looked at Mama. After just a minute or two, she looked at Papa again and hesitantly touched Mama’s cold face. She recoiled from this but didn’t run away. Callie watched this but wouldn’t come any closer than the parlor doorway. She stared at her mother in the coffin for a few moments, and then followed Iona as she left the room. Cyrus looked after them sadly.

“Sorry Papa,” Cora said.

He nodded and with tears streaming down his face, kissed his wife on the forehead. Cora went into the kitchen to allow him some privacy and give herself some time for her own weeping.

***

After the funeral the following afternoon, came the work of emptying the house so they could sell it and the farm. The plan was to move Cyrus, Callie, and Iona in with Cora and her family. Adding three people, instead of two, made the space problem even worse. Cora saw how crowded things were and worried about how her sisters would adjust, since they’d never lived anywhere other than the family farm.

The first few weeks made it seem like a mistake. Callie refused to leave the little room that was set up for them, and Iona spent most of her time by her side. Cora had to bring Callie food, clean her up, and try to soothe her terror at the unfamiliar sounds and smells in her new surroundings. And distressingly, Iona also seemed to regress. She and Callie stopped communicating with anyone but each other and often just sat silently together in their room.

Thankfully, Iona gradually began to come out of the room more often. And after about a month, Callie ventured out for the first time. Cora still had to feed her, and she would retreat to her hiding place at the slightest provocation, but it was still an improvement.

Cyrus, on the other hand, adapted well. He grieved for a month or two, as was expected and reasonable, but Oliver moved Cyrus’s favorite chair to the front porch, and most evenings he’d sit there and read out loud–occasionally from the bible but more often the newspaper or something written by his favorite author, Mark Twain. Eventually, even Iona and Callie would join them. Their neighbors would sometimes whisper and stare, hoping to catch a glimpse of those silent sisters (which was what people in Palmyra called Callie and Iona). Cora glared at them, but Cyrus just kept on reading, his voice steady and unperturbed.

***

As Callie and Iona continued to adjust to their new life, Cora could occasionally get them to take interest in some of the simpler chores–Callie would snap green beans, and Iona would sweep floors and hang out laundry. But despite these improvements, it was clear to Cora that they were spending more time in their room than they ever had when they lived on the farm. And Cyrus noticed it too.

“They’ve always had their own little world,” he said to Cora one time. “But it seems like it’s gotten a little farther away than it used to be.”

And he was right. With each new change in the household, Callie and Iona drifted even farther. The situation was driven home when Cora’s oldest son, Daniel (to whom the sisters had become accustomed) left home to take a job in Alton. Upon finding that he was gone, Callie and Iona retreated into their room and refused, for more than a week, to come out. They wouldn’t even join the family to listen to Cyrus read in the evenings

This understandably came to try everyone’s patience, Oliver most of all. He was especially annoyed when Cora had to do more and more to feed and clean up after the sisters. And to make matters worse, Cyrus’s health was beginning to decline, so she had to take care of him as well.

“You don’t have to put yourself through this, you know,” Oliver said to her after an especially difficult day.

She turned to him and managed, barely, to keep her response no more than emphatic. “I know exactly what you mean, but I still can’t abide the thought of putting my sisters in a place like that Lincoln School!

Then, that October, the stock market crashed. Cora fretted, remembering how her parents had been forced to sell off part of their farm during the financial panic of 1893.

“Carpentry is one thing that people will always need,” Oliver said, doing his best to reassure her. “I may need to travel a little farther to get enough work until things bounce back. We’ll make do.”

***

Things didn’t bounce back, however. In fact, they got worse. By 1932, more than two years into the Great Depression, there were far fewer opportunities for Oliver. He knew it could’ve been worse, but as he’d predicted, he had to travel (more than a little) farther to do enough to make ends meet. So at home, Cora had to shoulder more of the burden of keeping up with everything. She was grateful for help from her daughter Elsie, but she knew it wouldn’t last long. Elsie had a young man courting her, and Cora suspected there would be an engagement to celebrate before long.

And it didn’t take long for those suspicions to be confirmed. Elsie was planning her wedding for that March but had to delay when Cyrus died in his sleep at the ripe old age of 89 in late February. Cora consoled herself with the certainty that he’d had a good, long life and a peaceful end. Just as they had for Mama, she decided, they would hold his wake and funeral at home. It was what he’d have wanted.

***

With Cyrus gone, Callie and Iona withdrew almost completely. They spent most of their time in their tiny bedroom, sitting on their beds close together, signing to each other every now and then. On rare occasions, they would play one of their invented games, but when Cora signed to them to come out to eat or sit on the porch, one or both would return their sign that meant they were staying put. This left Cora with no choice but to nudge them, gently but insistently, as only she knew how. It worked, but Callie and Iona were grudging at best.

This soon led to them stopping caring for themselves almost entirely, Callie more so than Iona, which was a bit strange because Callie, like Cora, was 50, whereas Iona was 55. In any case, to a greater or lesser degree Cora had to feed and bathe them and help them in the bathroom. She tried to be hopeful initially, but quickly realized she had to resign herself to these new circumstances. She was exhausted and discouraged but made a point of remembering that Callie and Iona were family, and that she loved them.

***

By the beginning of 1934, only Cora and Oliver’s youngest son, Freddie, was still living at home. He was 13 and eager to quit school and learn carpentry from his father. Cora kept insisting that he finish his education, but deep down she knew it wasn’t going to happen.

Freddie’s zeal to go out and start earning money was largely due to how hard the Depression had hit central Illinois. The winter had been harsh, and many of the small farms had been sold off or just abandoned. This meant the number of people in the area was dwindling rapidly, so even if Cora could convince Freddie to finish his schooling, it was increasingly unlikely there would be a school where he could do so.

The harsh winter was followed by a dry spring and a brutally hot summer, so the cycle repeated the next year, as did the exodus of the population. This brought with it a new level of desperation for Oliver, so one night, after dinner, he sat Cora down and confided in her.

“I don’t know how long I can keep this going,” he said, looking and sounding as if he’d been beaten down. When he could find work, he often had to drive as much as an hour to get there, and more often than not, the jobs didn’t pay enough.

Oliver went on, almost pleading now. “Darlin’, I think we gotta move to Alton.”

Daniel, in his last letter, had told them that the Shell refinery there was looking for workers. And even if that didn’t work out, in a city the size of Alton, there would surely be more and better opportunities than in Palmyra.

Cora just nodded. There was no speaking around the lump in her throat. Oliver took her hands in his, rough and callused as they were. Then the tears she’d been holding back flooded out. She knew what was coming next.

“Daniel doesn’t have room for three extra people, much less five,” Oliver said. “And what with Callie and Iona’s needs…” he trailed off.

Cora wiped her eyes, and when she could speak again said, “It’s the Lincoln School, I suppose.” It was Oliver’s turn to nod, and Cora saw that his eyes glistened when he did so.

***

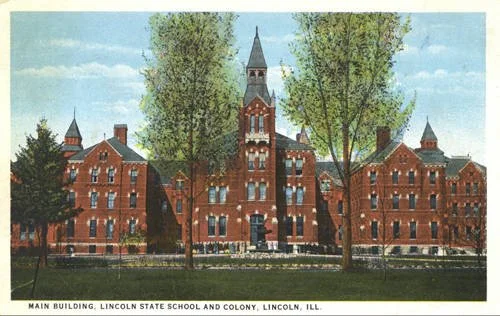

Things happened quickly after the decision was made, and just over a week later, they were started on the three-hour drive to the Lincoln School. When they arrived, Cora was filled with a mixture of dread and doubt. The administrative building looked cold and imposing, like the castle in that movie “Dracula” (which she’d hated).

A nurse came to greet Cora while Oliver got the two small, battered suitcases out of the trunk. To Cora, Callie and Iona’s fear and confusion during the trip had been palpable, which had broken her heart and worsened her guilt. She thought she couldn’t feel any worse, but then the orderlies came to take her sisters inside that awful building. Iona had been trepidatious, but after some coaxing, allowed herself to reluctantly be led away. Callie, on the other hand, had to be pulled up from the floor of the car behind Cora’s seat and carried off, struggling every inch of the way.

Iona watched all of this unhappily, and the last thing she did before going in the main door was to look back at Cora and make the signs for “what” and “why.” Her look of confusion and hurt would remain burned into Cora’s memory for the rest of her life. She signed back, trying to say that she would visit, but even as she did so, she doubted whether it would be possible. Then the main door closed and Callie and Iona were gone.

Cora couldn’t move–she just stared at the door. Oliver came and put an arm around her shoulders, and they stayed that way until she could stop crying. At last, he said, “Come on, darlin’,” and led her back to the car. She got in, and as they drove away, she looked back and wondered if she would ever see her sisters again. She didn’t.

***

Note: The Lincoln School and Colony (its full, official name) opened just outside Lincoln, Illinois in 1877, the year after Iona was born. At that time, it housed about two hundred inmates. And yes, they were inmates, because despite the name, it was an asylum, not a school. It grew quickly, especially with the 1915 law that made it possible to institutionalize anyone who was deemed “feeble minded,” as the term was in those days. The inmate population was used as slave labor and reached its peak of more than 5000 workers by the time Iona and Callie were admitted. It was an overcrowded, unsanitary environment that often resulted in illness and death. And although inmates occasionally received medical treatment, it was rarely sufficient and frequently was cruel.

Lincoln School & Colony Main Building; photo: Booth Library Postcard Collection, Eastern Illinois University

***

If Cora had known the true nature of the Lincoln School, it seems unlikely that she would’ve sent her sisters there, but the sad truth was that she didn’t know. So Callie and Iona were left in a strange, hostile place that terrified them.

Iona watched in alarm as Callie, still struggling, was carried off down a hall. She tried to follow, but an orderly’s strong hands gripped her arms and led her in the opposite direction.

“Come on, now,” he instructed her sternly, not knowing Iona couldn’t hear him.

He led her to a room, and then a woman came in and moved her mouth and pointed to her. When she didn’t move, the woman began undressing her. Iona realized it was time for a bath and moved obediently where the woman guided her. This wasn’t a nice bath like the ones Cora gave, though. The water wasn’t warm, the soap was smelly, and the woman was rough with her. Afterwards, the clothes the woman gave her were clean but stiff and scratchy.

The woman poked her in the back to make her walk. She moved her mouth and pointed at things as they went along. Iona saw other people wearing clothes like hers. Some of them were working, some were just sitting, and others acted like Callie–curled into a ball or hiding in a corner, their faces covered. She saw a boy about David’s age. His hair was the same orange color she remembered. Is this where their brother had gone? She waved to him, but he moved his mouth at her and hurried away.

They walked into a room full of beds. They were all close together like when they were all children at home, but this room was much bigger. Some of the beds had people lying or sitting on them, but most were empty, and they all smelled bad.

The woman moved her mouth and pointed at a bed, so Iona sat. She moved her mouth some more and then walked away.

Iona sat patiently, waiting for Callie to come and sit next to her on the bed. She would hide for a while, but that wouldn’t be too much of a problem–Iona would be able to comfort her.

To Iona’s great distress, however, it was more than a month before she saw Callie again, and then her sister was almost unrecognizable. She was much thinner, and it seemed like her senses were dulled. Iona would sign to her and would get a feeble response at best. But they were allowed to be in the same dormitory and even have beds next to each other. Sometimes Callie would curl up next to Iona or they would push their beds together… until the orderlies noticed and made them move the beds back to where they were before. In the morning, they would be woken up when it got light, just as it had been when they lived on the family farm. It was one thing that was familiar, but it was only a small comfort.

***

Iona ended up working in the Lincoln School textile factory, which produced all the clothing and linens for the institution and also made items to sell to the community. Iona’s job was to sweep the floor or carry bolts of fabric or bundles of clothing from place to place. It was hard work, and she tired quickly, but she soon learned that if she stopped or wandered off, she would be punished. So she did her work until someone motioned for her to stop. Then it was time to eat and after that, it was bedtime. It seemed like an endless cycle, and it’s a foregone conclusion that Iona, like all of the other inmates, never saw a penny of any profits the textile factory brought in.

Callie’s experience, however, was completely different. The doctors diagnosed her with schizophrenia. Subsequently, their reckless prescription was to subject her to electroshock therapy and severely restrict her diet, all of which served to drive Callie deeper inside her own mind and reduce her body to a withered shadow of her already lean self.

The separation and their living conditions took a great toll on both sisters. Iona became despondent and stopped working or caring for herself. Even the threat of punishment ceased to motivate her. Worse, Callie shut down entirely, responding with shrieks when anyone tried to touch her. Eventually, the staff gave in to what was clearly evident: the sisters had to be together if they were going to be the least bit manageable. So they were moved to beds next to each other and allowed to spend their free time together. After bedtime, they would often sit on their beds across from each other, signing or simply looking at one another. In the morning, it wasn’t unusual to find them together, pressed into one small bed, holding each other for comfort.

In 1941, even this small consolation was taken away when Callie died of pneumonia at the age of 61. Iona stayed with her throughout her brief decline, and then refused to move, despite being prodded by staff when it was clear that Callie was gone. She just sat and watched silently as they took her sister away.

After this, Iona listlessly continued working in the textile factory. Sometimes she would help tend to other inmates, but most of the time, she insisted on being alone. At night, she would sit on her bed in the same position she had with Callie. When she got too tired to sit up, she’d just curl up, despondent and utterly alone.

***

Iona lived six more sad, lonely years. During that time, the Lincoln School and Colony went through several changes, but she never noticed. She died in her sleep in 1947 when she was 70 years old.

The sisters were buried side by side in the school cemetery with a single marker that bears both of their names. And Cora not only didn’t get to see her sisters again but also was never able to visit their grave.

*

The colony closed in 2002 following decades of investigation and lawsuits. At that time, it was sold and became the Lincoln Correctional Center. This is how Callie and Iona Sheppard came to be buried in a prison cemetery. Together in death, just as they were in life.

Map showing the location of the Lincoln School (top), Palmyra (middle), and Alton (bottom) in Illinois