The Clothes Make the Woman

Clara Madigan loved to sew. That needs to be clear because it was the basis for the course of her life.

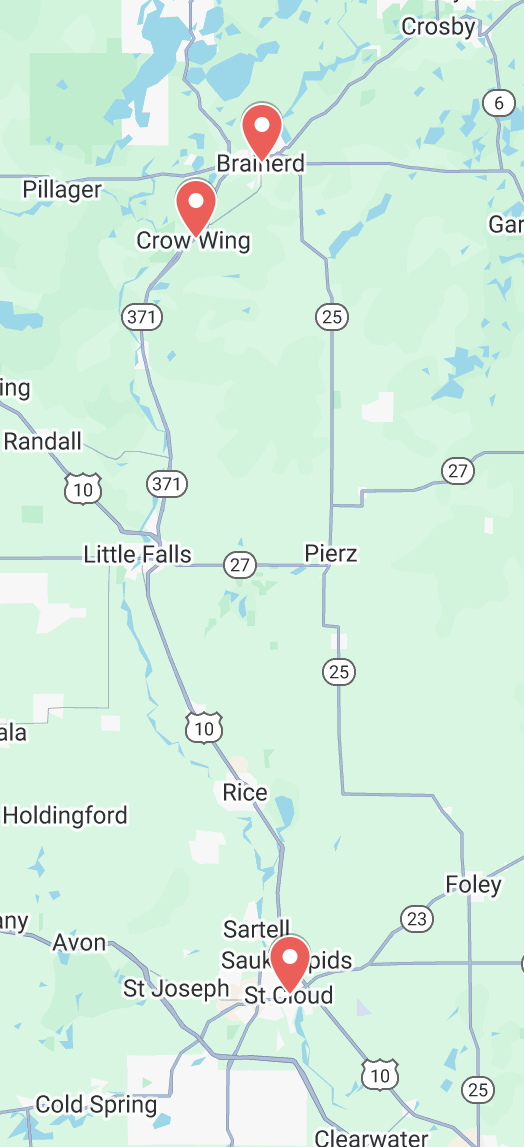

At a time (the late 1800s and early 1900s) when women weren’t considered competent to have minds of their own and conduct their lives as they saw fit, Clara was well-informed and politically active. She also started her own business and ran it successfully. And she accomplished this while juggling motherhood and the prejudices of being an Indigenous woman and a divorcee! A testament to her success is that to this day, the block in Brainerd, Minnesota where her shop stood is still referred to by her name. She was remarkable in many ways, but how did all of this come to be?

***

This story begins on a June day in 1851 when she was just 10 years old. Clara was carefully stitching a row of beads on a dress in the living room of her Auntie Jenny’s tiny house in Crow Wing, Minnesota. (Keep in mind that Minnesota was just a territory at that time.)

As mentioned, she loved to sew, and she also loved Auntie Jenny, an Ojibwe woman who had raised Clara’s mother, Camille. Auntie Jenny wore beautifully beaded moccasins and dresses she’d made herself, and she’s the one who taught Clara, and her sisters, how to sew.

She was watching Clara closely, and said in Ojibwe: “You have needles for fingers, little girl!”

Clara giggled and blushed.

An example of a girl’s clothing in the 1850s; photo: Pinterest

Her hair was in ringlets, and she wore a hoop skirt and half boots. By comparison, Auntie Jenny almost seemed to be from another world. And in some sense, she was–the Indigenous way of life was very different from that of the European immigrants. But it wasn’t something that Clara thought about much; she just knew her auntie was a kind and patient teacher. It was something that Rosemary, Clara’s five-year-old sister, didn’t appreciate (much to Clara’s annoyance).

“Can we leave now?” Rosemary whined for the third time. She wanted to go home and play. And as usual, Clara did the older-sister thing.

She sighed dramatically and put down her work. “Oh all right.”

Auntie Jenny chuckled and said, “Come on, I’ll walk you home.”

***

Clara was a little pouty herself on the walk home. She’d insisted that she was old enough to walk by herself, but both her parents and Auntie Jenny wouldn’t hear of it.

“I won’t get lost,” she’d told her mother in a conversation just a week before.

“Obey your mother!” her father Alec, had scolded.

Camille, knowing how headstrong Clara could be, took a different approach.

“You know your way around very well, but Crow Wing has so many visitors every day. Some of them aren’t very friendly, and we don’t want them to give you any trouble.”

Clara thought about that conversation as she watched the wagons rolling in from the Red River Trail. The squeal of the wooden wheels, along with the mix of voices speaking French, English, and Ojibwe, were the constant backdrop of Crow Wing. It was just a small town in 1851, but it was also an important crossing point on the Mississippi River. And even though the official population was just a few hundred, many more people were passing through on a daily basis. And this, combined with an abundance of cheap liquor and gambling, meant that crime and a certain harshness were an ever-present part of the local landscape.

As Jenny, Clara, and Rosemary approached the turn that would take them home, they heard people yelling in French near the river. Two men were arguing, then others joined in, and soon it was a brawl. A couple of Ojibwe men ran past and stepped in to try to break it up, to no avail. Clara was fascinated and tried to stop to watch, but Auntie Jenny hurried them along, and shortly, they arrived back home without further incident.

Clara was annoyed though. She was convinced her auntie, and parents too, were making a bother about nothing: a conviction that would continue to grow.

***

And so it was that Clara’s independent nature, and a certain willfulness, became more and more apparent in ensuing years – much to the dismay of her parents, especially her father. He wanted what was best for her, of course, but Clara was in rather pointed disagreement with him about what that entailed, which was brought into sharp relief as she read the local newspaper.

It was just a week before her sixteenth birthday, and over the last year or so, Papa had become increasingly strident about her finding a husband.

She had gotten absorbed in an article about the Minnesota Territory drafting a constitution for statehood, so she was startled when her father’s voice came from behind.

“I hope you’re reading the society pages,” he said.

Alec was a county commissioner and one of the founders of Crow Wing, so he was well-informed about what would soon be state politics. The problem was that he wouldn’t discuss any of this with Clara. It was an endless source of friction between them. More than once he’d told her: “Politics is no place for a woman. You need to learn to be a good wife and mother. Leave the governing to the men.”

But Clara stubbornly refused to do that–she covertly, but voraciously, read any newspaper she could lay her hands on.

She sighed, threw the newspaper onto the table, and started to argue with him but decided against it. As much as this ongoing fight angered her, she also wanted to keep the peace.

“Yes, Papa,” she said tersely as she brushed past him on the way to the room she shared with Rosemary and Libby, their youngest sister. She had a stack of sewing projects she was working on, mostly alterations for her siblings, but there were also some projects for people in town. She made a little bit of money doing that work and was secretly stashing it away. One day, she hoped to buy one of the new sewing machines. They were expensive, but she’d read they made sewing much faster and did a nice job.

She picked up a pale yellow dress that she had made for her sixteenth birthday party. Camille walked in and said, “It’s beautiful, Clara.” After an awkward pause, she went on. “Thank you for not fighting with your father. He means well.”

Clara managed a smile but couldn’t manage to make it convincing, so she simply nodded.

***

It was more than five years later that Clara came across her yellow birthday dress while digging in the depths of her wardrobe. The day was unusually warm for mid-September, and she thought, for the umpteenth time, about how corsets were never comfortable in hot weather, even when they were nicely fitted.

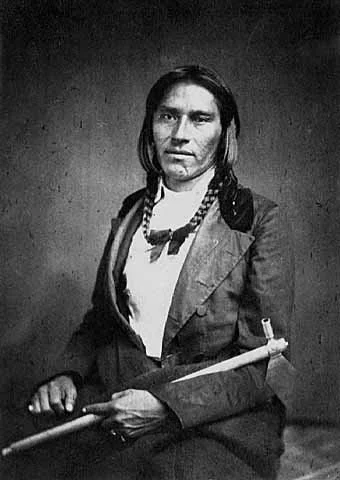

Chief Hole-in-the-Day (Bagone-giizhig); photo: Minnesota Historical Society

But what was uppermost in her mind was the reason she needed to find a dress: they were going to see Chief Hole-in-the-Day arrive in Crow Wing with his entourage of tribal officials. Almost everyone in town was going to be there, as if they were watching a parade. Mama and Auntie Jenny would be with her, along with her brother and sisters, but Papa would not. And for once, Clara agreed with his reasons wholeheartedly. Hole-in-the-Day was coming to Crow Wing to try to resolve a volatile dispute over government annuities that were stolen from the Ojibwe, and Alec was working with other town officials to support him.

This was offset when she recalled her father’s most recent reprimand: “You’re twenty-one! You should be married and having children by now!”

She took a breath and forced herself to remember how they were in uncharacteristic agreement over the annuities issue. It was partly principal and partly practicality. Papa got some of the annuities on behalf of the family, and they did help but weren’t vital. For some relatives, however–she thought of Auntie Jenny–the annuities were a matter of survival.

***

Three days later, Clara was horrified to hear how several white men from Crow Wing had burned down Hole-in-the-Day’s house just a few miles outside of town. Soon, she heard the front door open and went to the front hall.

“Are the Ojibwe going to war, Papa?” she asked

“Oh for heaven’s sake, girl,” Alec snapped. “Why don’t you go work on your dresses?”

“I will later. Can’t you at least tell me if there’s going to be a war?” she replied.

Alec glared at her, looking ready for a full-blown argument, then sighed. “No, there won’t be. They came to an agreement. The annuities will be paid.”

Clara was going to ask more questions, but Alec stomped off before she could. She went back to her room and sat down at her sewing machine. It wasn’t really new by now, but it was by far her most cherished possession. She brushed her fingertips over the wooden base where she had painted “Clara Madigan, 1862.” It had taken a while for her to learn to use it: loading the bobbin, working the treadle, feeding the cloth under the needle and coordinating it with the foot action that made everything work. It was mostly trial-and-error. (The instructions that came with it weren’t very good.) But she was a quick study. One of the biggest surprises was how noisy it was: the vibrating thump of the treadle and the clack of the needle. But she quickly got used to it and was delighted to find that the advertisements were true; it did make work go much faster. At first, Papa had objected, calling it a frivolous waste of money, but when faced with Mama’s enthusiastic approval, he’d relented. “I suppose it’ll help you put together your trousseau,” he’d grumbled.

She smiled, relishing the memory of the small victory, and went back to her sewing room to tidy up for the sewing circle she hosted. They’d be making bandages for the soldiers serving in the Civil War that was raging out east. She was thankful to be far away from the battles and that none of her family or close friends had gone off to fight, but it was still important to help, and the best way for her to do so was to make bandages and blankets and clothes for the soldiers. She finished by piling a bundle of cloth, and then went to get the tea set. Her guests would arrive soon.

***

Eight years later, when the Civil War was long over, Clara had, by her own choice, done as her father wished. She was married and had two daughters: Lolly, who was five, and Ellen, who was almost three.

As was often the case, the sound of running and giggling from down the hall compelled her to get up from her work and listen at the door of her sewing room. Lolly and Ellen loved to thunder around the house, but they had demonstrated, more than once, that playing could turn to fighting at the drop of a hat.

As soon as she was satisfied that open warfare wasn’t imminent, she went back to her new sewing machine, a recent gift from her husband Caspar. (She appreciated it but suspected that he now regretted giving it to her.) The first thing she’d done when she received the new machine was to paint “Clara Greninger, 1870” on the base. She’d decided that this would be a tradition with her sewing machines.

She was still getting used to the new house in St. Cloud. Moving from Crow Wing had made her uneasy, but she didn’t have a say in it–when Caspar became the St. Cloud Sheriff, the decision was made. The silver lining, however, was that the move had been good for her sewing business. St. Cloud was a larger town, and women in the community had taken notice of her skills. She was earning as much as $10 a week and still had time to take care of Caspar and the girls. Even so, it had become a point of contention in their marriage. Caspar wanted her to give it up entirely. Like her father, he had definite ideas about a woman’s place.

“I don’t want you doing all that work for everyone else, Clara,” he’d told her just the week before. “It tires you and it’s not proper for you to be working. I make enough to support us. You don’t need to earn any money.”

“I do this because I want to, Caspar, not because I think I need to!”

At that point, Caspar had unwisely switched to being patronizing. “I don’t want to upset you. I just want what’s best for you and our children.”

Clara was more than willing to keep arguing, but she knew from experience that it was pointless and didn’t want to waste her time and energy. She was still angry but managed a small smile and nod. Caspar mistakenly interpreted her smile as meek acquiescence and didn’t notice the hint of smugness that accompanied it. Clara thought, not for the first time, that being so profoundly obtuse probably wasn’t the best trait for a sheriff. Caspar, apparently determined to underscore that thought, gave her a condescending smile and pat on the shoulder, then left the room.

1870s fashion plate; image: Wikimedia Commons

Clara was seething in the wake of his exit but calmed herself with the thought of how being underestimated was often useful. She was sure that any notion that she would keep a secret had never crossed Caspar’s mind. And of course she did have a secret, namely that she wasn’t turning over all of her earnings to him. Yes, it was what she’d agreed to when they got married, and she’d abided by it for the first few months. But Caspar, instead of quieting down and letting her do her work, had become more and more strident and arrogant with his complaints. Given that there was no use trying to discuss it with him rationally, and that the constant quarreling was taking a toll on their relationship, stashing away money was a way for her to feel a sense of control.

She looked at the stack of dresses she was working on and felt more optimistic than overwhelmed. Dress styles were changing from hoop skirts to bustles, so business was actually increasing. But this was an example of how Caspar being unobservant worked in her favor: he didn’t pay attention to how much her business had increased, so he didn’t notice that the money she turned over to him also hadn’t increased.

Any hope of continued peace and quiet was shattered by an indignant squeal from somewhere down the hall. It sounded like Ellen. Clara sighed and went to tend to her daughters. She glanced out the window; it was chilly but sunny, so she thought she would bundle them up and take them to the park where they could play outside.

***

This strained situation between Clara and Caspar continued to deteriorate and was worsened when Camille died of tuberculosis (or consumption as it was called then) in 1873.

Clara was at her father’s house packing dishes into a crate but stopped and motioned for Rosie, who was looking and acting cross, to stop as well.

“You did a good job taking care of Mama this last year,” she said. “I’m sorry I wasn’t there to help.”

Rosemary squeezed her hand. “That’s all right. You were taking care of your own family. And you were there to say goodbye and help with her funeral…” She trailed off looking troubled.

Clara was puzzled. “I thought you were angry about me not being here when she was sick.”

Rosemary shook her head.

“Then what’s the matter?”

Rosemary was hesitant and looked around the room anxiously. Finally she leaned in close. “You mustn’t tell Papa.” She looked and sounded desperate.

“Of course, but–”

“I’m expecting,” Rosemary whispered.

Clara’s eyebrows looked as if they were climbing off her forehead. It took a few moments before she could give voice to the first question that came to mind. “You’re getting married then?”

Rosemary shook her head no.

“But…Harry. You said he was going to propose. What happened?”

Rosemary shrugged. “I thought he was. I was sure. Then…” her voice broke and tears followed.

Clara went and put an arm around Rosie’s shoulders. They stayed that way until Rosie could speak again. She took a deep breath. “He told me he didn’t want to see me any more and… just… left.” Tears threatened to flow again, but she fought them off with a shake of her head.

Clara held her at arm’s length and gave her a fierce smile. “Then good riddance. If the fool doesn’t appreciate what he had, he doesn’t deserve you!”

She paused and leaned in conspiratorially. “I have news too, and I’ll make you a deal: I won’t tell Papa yours, if you won’t tell him mine.”

Now it was Rosemary’s turn to be amazed. “What is it?” She stopped mopping her eyes with her handkerchief, distracted by curiosity.

“I’m divorcing Caspar,” Clara said. Rosemary started to respond, but Clara cut her off. “He just left. Like Harry. Except I got no explanation. I don’t even know where to send a letter.”

Rosemary considered this then gave her a familiar, sly smile. “He’s just as big a fool as Harry.” Clara laughed and gave her a hug. A few more tears fell, then they agreed to be done with it.

“There’s one more thing,” Rosemary said at last. Clara just nodded and thought, I’m sure I can’t be amazed by anything else today.

“I want to move to Brainerd with you.”

So I was wrong, Clara thought but said, “Well, of course, but what about Papa? He’s expecting you to move to White Earth.”

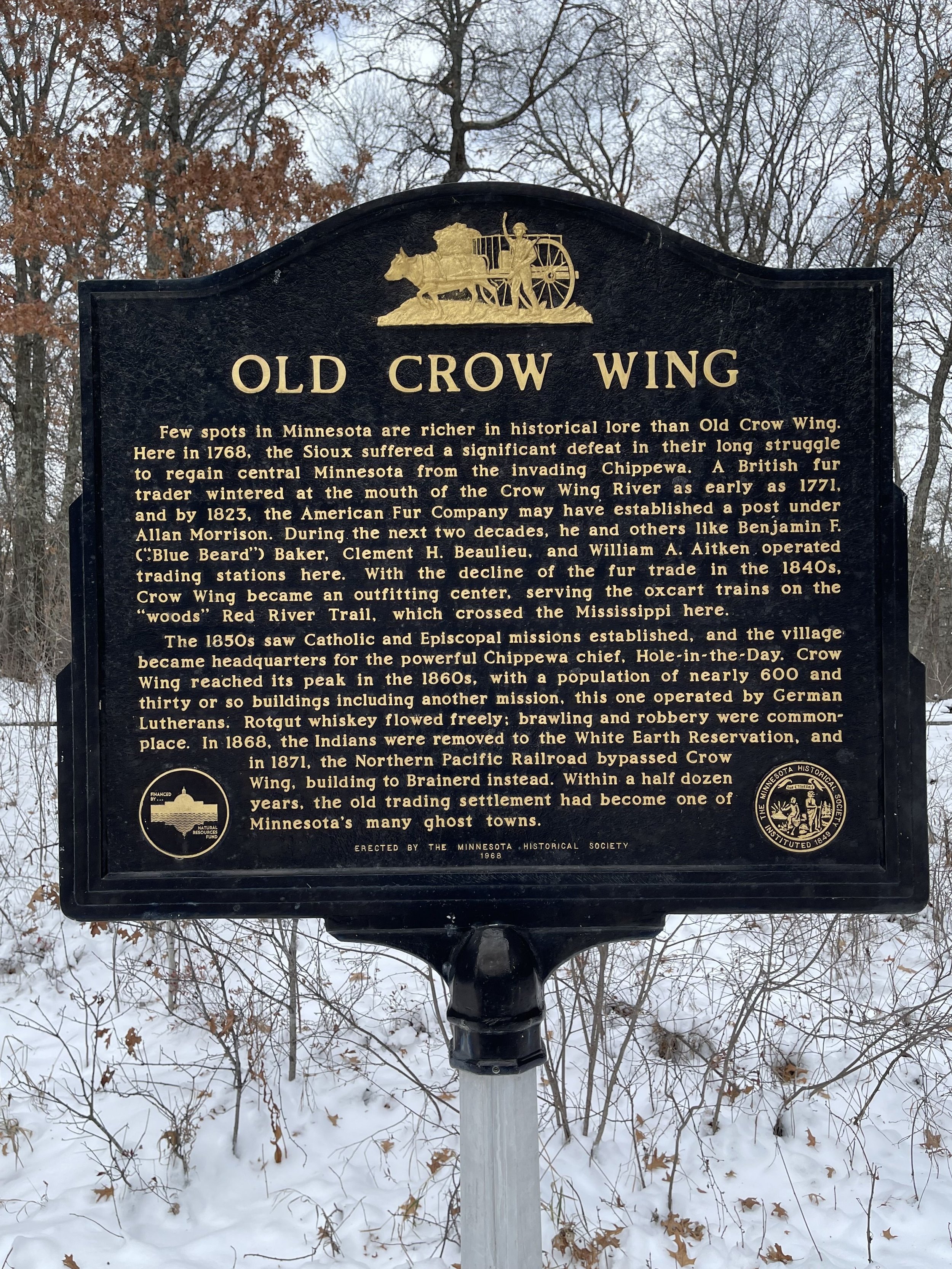

Crow Wing historical marker; photo: The Historical Marker Database/Liz Koele, 2021

Clara was proud that her father had stayed in Crow Wing as long as he had, but there was no point now. Six years ago (in 1868), the railroad had decided to put the new crossing in Brainerd (10 miles to the north) instead of Crow Wing, and she knew then that it was her hometown’s death knell. It was also, she recalled bitterly, the same year the government had required the Indigenous population to relocate to reservations. For the Ojibwe in Crow Wing, that was the White Earth reservation. To make it all so much worse, it was around that time that Mama had come down with consumption.

That was the main reason Papa had held out so long–Mama knew she was dying and wanted to spend her last years in Crow Wing. The family all respected that decision, but Mama was gone now, and her death seemed to mirror that of the town. Papa had taken that as a sign it was time to finally move to White Earth, and he expected Rosemary and their youngest brother and sister to go with him.

Clara and Rosie both jumped when Papa yelled at one of the men he’d hired to help with the move. It was the first time they’d heard him sound like his old self in a long time. Clara wasn’t sure she liked it but understood – it kept his mind off Mama.

*

Not long after their mother’s funeral, Clara and Rosemary got a letter from their father. Rosemary read it out loud, and when she finished they both were a bit stunned, but pleased too.

“I’d never have thought he would react this way,” Clara said, shaking her head.

“It’s nice to be surprised once in a while,” said Rosemary.

Alec, upon learning of their situations, wrote to tell them he was not angry with either of them, but he was disappointed in their men. He went on to offer to pay to move them to White Earth so he could look after them and his granddaughters.

“Do you want to?” Rosemary asked.

Clara considered this, but only for a moment. “No. Do you?”

Rosemary thought for a few seconds, then shook her head.

They looked at each other and shared a relieved laugh. “Well, we’ll have to find a way to break it to him gently,” Clara said at last.

Later that night they did exactly that. In their reply, they thanked him for his offer but declined, assuring him that they would be fine – they had each other, and he and Mama had taught them well.

***

It was only six months later (early in 1874) that the sisters were given reason to celebrate–Rosemary gave birth to her only child, a daughter. And even though Clara had seen many infants, including her own daughters, she still couldn’t stop looking into her newborn niece’s crib. The baby was sleeping, so she had to resist the urge to caress the fuzz of black hair.

She looked over to her sister who was pale and exhausted, which was to be expected, of course. “Did you decide on a name?” she asked

“Alice,” Rosemary said.

Clara stayed for a few more minutes until Rosie went to sleep, then retreated to her sewing room. She had intended to work on one of the many dresses stacked about, but found her eyes (and the rest of her) weren’t up to it. So she sat in her rocking chair and indulged in some reflection. The way she and Rosie had described their situation to their neighbors when they moved to Brainerd still gave her a pang of conscience, but she knew it was for the better. It was true that 1874 was showing the beginnings of many changes in society, but being divorced was still at best unseemly, and having a child out of wedlock was immensely scandalous. So, when asked, they both said simply that they were widowed: Caspar, so it went, had died many years ago doing his duty as sheriff, and Rosemary’s husband had recently been killed in a farming accident. So they had moved to Brainerd together to restart Clara’s dressmaking business with Rosemary handling the accounting. And the story had worked–it was also unseemly to pry very far into a widow’s circumstances.

They were still a bit of a novelty, given that no men were involved in the business or household (which made Clara quietly proud), but that was quickly outweighed by the fact that the local women greatly appreciated having a skilled dressmaker in town. And with that satisfied thought, she went to get ready for bed.

***

By 1885, Lolly was twenty and had added millinery (the term for hatmaking) to the offerings at Clara’s shop. She looked up from where she was sewing flowers and ribbons onto a hat. “What, Mama?”

“I said,” Clara repeated, “you have needles for fingers.” She’d hoped for a laugh but saw only polite dismissal. Lolly was apparently too old to be amused by such things. “It’s something your Great Auntie Jenny used to tell me,” she said with a sigh.

Lolly just nodded and went back to work while Alice, now ten, watched, completely captivated.

The room was filled with the thump and clack of Clara’s sewing machine. Strange that none of them will know the time before these things, Clara thought. Still, she was glad she’d insisted on both Lolly and Ellen learning to bead and sew in the Ojibwe tradition as Auntie Jenny had taught her–it was a good way for all of them to connect to that part of their heritage, and it had turned out to be key to Lolly’s interest in hatmaking. Clara approved wholeheartedly and was happy to see Alice taking an interest as well. It might just be that the little girl idolized her older cousin, but she also seemed to enjoy the small tasks Lolly let her do.

She turned her gaze to Ellen, who was sitting on the couch reading the paper. It was annoying that she didn’t appreciate how lucky she was to be able to pursue her interest in politics. It was even more annoying that the girl was so blatant (at times condescending) about her complete lack of interest in dressmaking. Perhaps it was because she had no talent for it, but whatever the reason, Clara had given up continuing to instruct her after she’d grudgingly (and with much whining) struggled through the basics.

Suffragists holding a sign; photo: Lake Agassiz Regional Library

“What’re you reading about?” Clara asked.

“There’s a new suffrage group,” Ellen murmured, nose still buried in the paper.

“Is that the one run by Susan B. Anthony?”

This got Ellen’s attention. “Yes,” she said, her surprise clearly evident.

Clara heard this and was piqued. The clack and whir of her sewing machine stopped, as did Lolly and Alice, their eyes fixed on Clara.

“Listen here, young lady.” Clara’s tone was sharp. “I was following politics long before you were born. And I had to battle your granddad to do it.”

Ellen was taken aback but soon recovered. “Maybe so, but dress reform just isn’t as vital as suffrage. Dress styles aren’t going to change the world. Getting women the vote will!”

‘It doesn’t have to be one or the other!” Clara argued. “How can we speak up for ourselves in clothes that make it hard to breathe?” She pointed to her corset. “Did you ever notice that I’ve always tried to make dresses as light and comfortable as I can?” Ellen was tight-lipped and didn’t reply. “Did you ever stop to think that if we can move about more freely, maybe we can think and act more freely?”

“That may be true–” Ellen began, but Rosemary, who’d entered in time to hear Clara’s outburst, intervened.

She took Clara’s hand and said: “How about we two go for a walk?”

Clara reluctantly allowed herself to be led from the room, and as soon as she and Rosemary were gone, Lolly quipped, “Time for Aunt Rosie to step in… again.” Ellen just raised an eyebrow and went on with her reading.

***

For several years, Clara and Ellen continued to periodically lock horns, but they always reconciled… albeit grudgingly… and with intervention by Rosie.

But despite these quarrels, the shop was quite successful, and in 1898, they bought a new store sign that said “Greninger’s Millinery and Dress Making” in fine gold lettering on a green background.

“What do you think?” Clara asked, turning to Lolly.

Lolly smiled and gave Clara a hug. It was a sweet gesture, but there wasn’t much strength behind it. She just keeps getting more and more frail, Clara thought, trying to keep her worry from her face.

“Let’s go inside, and I’ll fix us some tea,” she said. Lolly nodded and worked to catch her breath. Clara had been hopeful when Lolly recovered (more or less) from scarlet fever, but then she’d come down with rheumatic fever. They’d gone to several doctors and clinics, but the news was all the same: Lolly’s heart was failing and there was nothing that could be done.

Illustration of Clara wearing one of the hats made in her shop

Clara had wanted to close the shop to concentrate on caring for her daughter, but Lolly had been adamant. “I want to keep working as long as I can, Mama!” she’d insisted. And Clara had gone along: it was true that the happiest times for the family were at the shop. Clara, Lolly, and Alice worked on dresses and hats while Rosie and Ellen tended to the business side of things. This division of labor helped everyone get along. And there was also an unspoken agreement that keeping the shop afloat had to take priority–for Lolly’s sake, if nothing else.

When Clara and Lolly got inside, Ellen hurried to help. They got Lolly seated in the office where Rosie already had a pot of tea brewing. Sitting in a chair with a steaming cup, Lolly was soon breathing more easily and waved Alice over. “Show me that hat, cousin! Those feathers are lovely!” Alice, who was 23 now, beamed and brought the hat over. She’d been learning from Lolly and Clara for most of her life and was proud of her work. She’d found, just as Lolly had, that Clara’s teaching had made all the difference.

It was hard for Clara and Rosemary to watch, though. They knew times like these were numbered. And as if to highlight that sad truth, Lolly soon signaled it was time to go home. Once they were there, Clara helped her settle into bed, propped up on pillows to help her breathe more easily. “I made some notes about what I’d like for my funeral, and the dress I’d like to wear,” she said at last. Clara just nodded, unable to speak. She took Lolly’s hand and gently kissed her swollen fingers. “It won’t be long now,” Lolly whispered.

And she was right. The next morning, Clara saw that Lolly was visibly weaker, and sent word for Rosemary, Ellen, and Alice to come right away. They sat with her, holding her hand, reading out loud, and telling stories from the shop. She was lucid but drifted in and out of sleep, and early the next morning, drifted into a deep sleep that didn’t end.

Lolly was buried in her favorite dress–one Clara had made for her–with the hat she’d admired just a few days before laying on her chest. Clara was the last to say her final goodbye. She carefully smoothed the lace on Lolly’s collar and kissed her one last time.

***

Lolly’s death affected everyone in the shop deeply, and it took months for them to get back to normal. But they did, although it was a new normal where the younger generation took on more responsibility in the shop. Which, unsurprisingly, resulted in occasional frustration…

“Mrs. Quinn just won’t quit fussing about the skirt hems,” Alice said, shaking her head in disgust. She and Ellen were in the middle of the shop amid stacks of dresses and hats in various stages of completion.

“I told you she would,” Ellen said. “When she signed the contract, she was adamant that the dresses for the play can’t show any ankle.”

Alice folded her arms and made it clear she would not back down. “But that’s not the way the styles are now!” She pointed to the hem of her own skirt that was clearly above her ankles.

Hazel, the hatmaking assistant, looked as if she wanted to comment. She sat at the work table across from Polly, who’d been at the shop longer and knew when to stay quiet. Which was fortunate for Hazel. Polly caught her eye and shook her head, then leaned forward and whispered, “Stay out of it, if you value your life.”

Clara watched and drew her shawl tighter. Not so long ago, she would’ve joined in the fray, but she’d caught the flu right after Christmas and was taking a long time to get back on her feet. Besides, she’d be celebrating her 75th birthday in April. Time to leave these arguments to the youngsters, she thought.

Her illness had prompted Rosie to finally have a conversation about stepping aside and handing the business over to Alice and Ellen. With Hazel and Polly (who Clara had taught until she’d gotten sick) the orders were covered, and, despite the occasional tiff, they all worked well together. Although, Rosemary observed, that couldn’t be proven by the scene unfolding in front of her.

“Alice,” she said firmly enough to give her daughter a start. “I think Hazel and Polly have some questions.”

Alice shot her a not-so-charitable look, then turned it on Ellen (who’d also quieted down), and then, with a dramatic flourish, moved to her assistants.

“Ellen–” Rosemary began but couldn’t finish before her niece strode into the office and not quite slammed the door.

“You know,” Rosemary said to Clara, “they remind me of you and Papa.”

“Oh?”

Rosemary laughed. “Of course. Both of you hard-headed, bound and determined to do things your own way.”

Clara gave this a moment of thought. “And you’re the peacemaker, just like Mama was.”

It wasn’t something Rosemary had considered, but now that Clara mentioned it…“Hmm, I guess so.”

They sat for a while longer, sipping tea in companionable silence. Or near silence: there was still the familiar clack, whirr, thump of the sewing machines that Clara found so comforting.

“You know, Rosie, “ she said at last. “I’m going to miss this so much.”

Rosemary nodded and dabbed at her eyes with a handkerchief, whereupon Clara produced her own handkerchief for the same purpose. Shortly, she patted Rosemary’s hand. “Let’s go home.”

Front Street in Brainerd, MN. Clara’s shop was on this street; photo: Crow Wing County Historical Society

***

Rosemary, Ellen, and Alice stood in line outside the polling place for the 1920 presidential election. They were elated and proud, if a touch nervous. They knew, as did all of the women there, how monumental this vote was–nothing would ever be the same! It was a heady feeling, almost surreal. But just behind all of that was a sadness that made Rosemary suddenly quiet.

“What’s wrong?” asked Ellen.

Women in line to vote in Minneapolis, c1908 (probably a local school board election); photo: Minnesota Historical Society

Rosemary sighed. “She’d be so proud.”

Alice and Ellen just nodded, remembering that Clara–who’d died just a year ago last January–had insisted, even at the end, on sewing, and she liked it best when they’d read the paper to her while doing so. She seemed to know she didn’t have long and wanted to make the most of the time left. The progress of the 19th amendment was especially important to her, but to everyone’s heartbreak, she passed away before it was ratified.

Rosemary fingered the lace cuff of her white dress and realized all three of them were wearing similar dresses that Clara had made in honor of the suffrage movement. Then she looked around and wondered how many other women were wearing dresses sewn by Clara. More than a few, she guessed. And with that, her spirits lifted–she could almost feel her sister standing with them.

Then Alice was tugging at her arm, beaming. “Come on. We’re next!”

And together, all four of them, went forward to make history.

Map showing Brainerd (top), Crow Wing (middle), and St Cloud (bottom); Google Maps