A Soldier’s Path

Written by Eric Shipley & Charlotte Easterling

August 22nd, 1862

Landon fidgeted under the late summer sun of Athens County, Ohio as he stood in a line of men waiting to enlist in the Union army. His older brothers, George and Liam, had signed up a year ago. Landon had wanted to lie about his age and join up with them, but they had insisted that he wait so he could help out on the family farm for another year. Landon had agreed but only grudgingly so.

He wiped sweat from his shock of dark, curly hair and fanned himself with his hat. He wasn’t especially tall, but his frame was lean and wiry strong from having done farm work his whole life.

The man behind him, a neighbor named Curt Blasedell, muttered, “Reckon we oughta get used to being uncomfortable. Being in the army’s a far sight worse from what I hear.”

“Yep,” Landon agreed. “I believe you’re right.”

There were many other familiar faces, almost all from farms in the county. They were mostly 18, like Landon, or maybe 19. (A few were a little older, but not by much.) Landon had talked with some of them and found that they shared many of the same reasons for enlisting: wanting to defend the Union, needing steady pay, and some were simply looking for adventure. Many admired President Lincoln, just as Landon did, and didn’t believe any state had the right to secede. And there was the slavery question. Ohio wasn’t a slave state, and his family had never owned slaves. They weren’t reformers or radicals, like those abolitionists, but his folks had always taught him slavery was wrong. That was one reason he respected the President so much.

Portrait of Landon Baird. Illustration by Charlotte Easterling.

The newspaper had often published stories about Lincoln and his speeches and such, so there was no doubt he hated slavery and loved his country. He was clearly determined to keep it united. Or see it reunited, as that was now what was needed.

Landon had talked with his family about all of this, and they accepted it. What he hadn’t talked about was the fact that he wanted to get away from the farm and experience life. He’d been born smack dab in the middle of a passle of brothers and sisters and often felt lost in the shuffle.

The line moved forward and he was at last at the table where he would sign his enlistment paper. A tired-looking Union soldier asked some questions and filled in the open spaces, then pushed the paper at him and handed off a pen.

“Sign your name or make your mark there,” the soldier said curtly and pointed at the line for his signature.

He was proud that he could read and write, and took a moment to look over the terms of enlistment. The soldier cleared his throat impatiently and looked exasperated, so he dipped the pen in the ink bottle and, with a flourish, signed his name: Landon K. Baird.

September 9th, 1862

Photo of a Union camp during the Civil War. Photo: warfarehistorynetwork.com

Camp Marietta, where the 92nd Ohio Infantry Regiment was stationed, was pretty much what Landon had expected–muddy and dank with lots of tents and rough shacks, but it was actually no worse than the camp where he’d done his basic training.

He took out his orders and showed them to the guard standing duty at the entrance.

“You’ll be wantin’ to check in with Colonel Putnam,” the guard said and pointed out a shack in the distance. Landon thanked him and trudged off with his small pack. He hadn’t gotten very far when he heard…“Well now, boys, I do believe we got us some fresh fish!”

This from a grizzled soldier of indeterminate age (in a tattered uniform and kepi) who sniffed the air dramatically. This brought chuckles from other similarly grizzled soldiers of indeterminate age (in similarly tattered uniforms and kepis) who stood with him outside what looked to be a mess hall.

Landon felt his face redden. George and Liam had warned him that “fresh fish” is what the older soldiers would call him as a new recruit, but it still made his self-consciousness about being so fresh-faced that much worse. He briefly considered a biting response but decided, wisely, to stay on the way to report to his commanding officer, one Colonel W.R. Putnam who was a lean, older man with graying hair and beard and a stern demeanor.

“Welcome to the 92nd, Private. Go get your uniform, and kit, and ordnance,” he said brusquely. “Get a bunk too. Dinner’s in an hour in the mess you must’ve passed getting here. Better get a move on.”

“Yes, sir!” Landon replied with a salute. He got a perfunctory handshake and was dismissed.

He was glad the meeting had been so mercifully short, and actually, it ended on a good note. He was on his way to get his uniform! It was something he had been looking forward to… until he tried it on. It was hot and itchy, and it didn’t fit well.

This was when he truly came to appreciate his “housewife.” Not a real woman (although he sometimes wished it was), no, “housewife” was what soldiers called their sewing kit. Liam and George had told him to take it when Ma offered and to thank her for it. He had done so but now resolved to thank her again in his next letter. Without those needles and buttons and thread, there was no way he’d make his uniform fit and keep in good repair. So he’d done his tailoring, and then he sat for his first photo (a Daguerreotype) in his uniform, looking proud but a little apprehensive too. In years to come he would look at that photo and reflect on how the apprehension was altogether reasonable.

September 17th, 1863

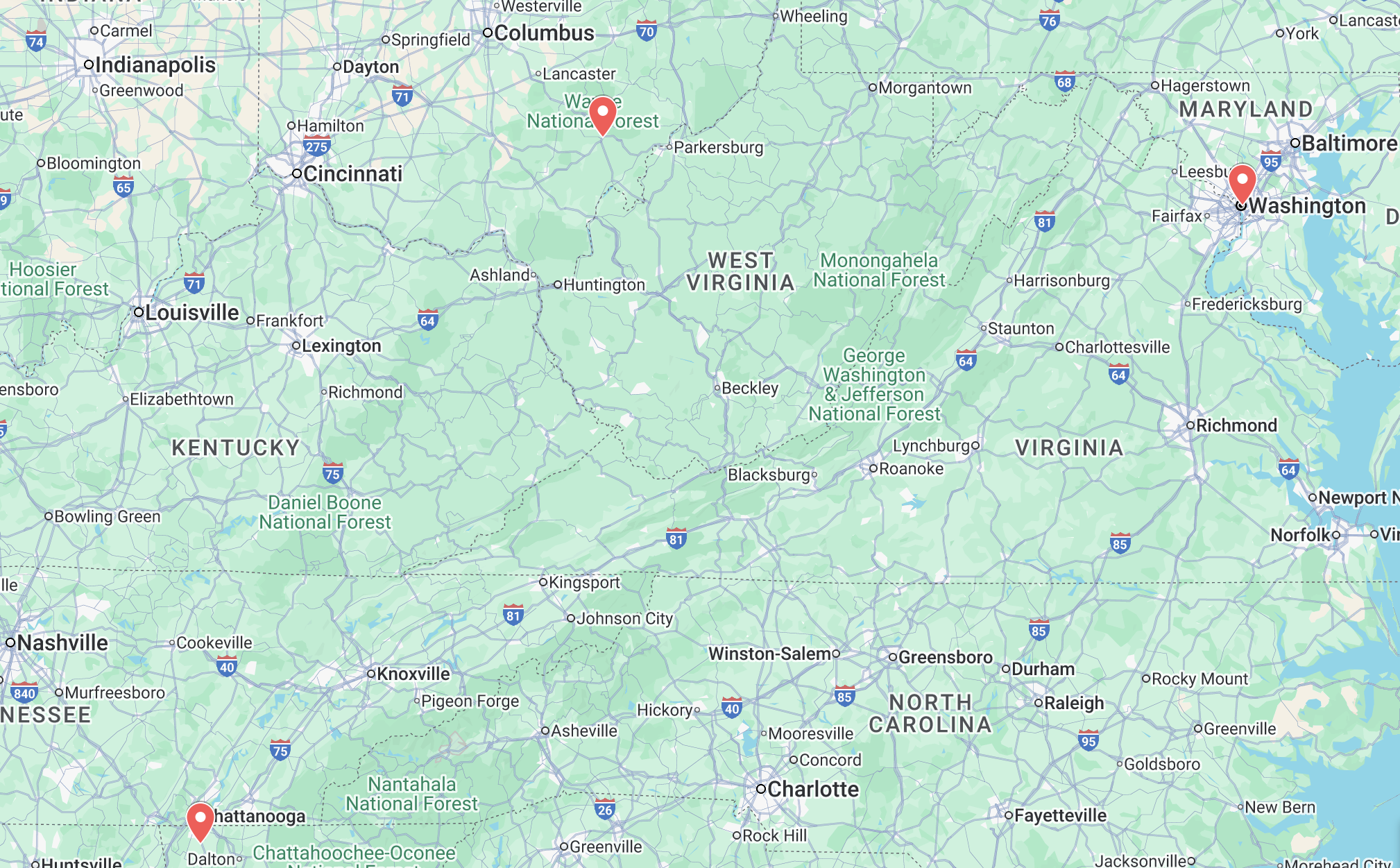

The 92nd was stationed at Chickamauga, Georgia, about 12 miles southeast of Chattanooga, Tennessee. They’d be moving out first thing tomorrow morning with three other Union regiments, marching to battle with the damned graybacks at Chickamauga Creek. It wouldn’t be Landon’s first real fight, so he knew what to expect, or at least he thought he did. He couldn’t figure out why, but he felt the same strange mixture of excitement and terror at the prospect of another battle.

At least it’ll break up the boredom, Landon thought, then remembered what he’d seen in the field hospitals when he’d helped carry wounded. How could he be excited about an engagement that could leave him dead or with some gruesome wound like he’d seen? The prospect of being in the hands of the sawbones (army surgeons) made his stomach churn. They got the “sawbones” nickname because their favored tool was the bone saw. For amputations. And the agonized screams that came with those amputations always lurked at the back of his mind.

He shook his head, trying to clear it, and looked down. There were his muddy, damp boots, which brought another remembrance–early on, his brothers had given him emphatic orders to take care of his feet! And Landon had learned the wisdom of those orders. So, instead of just sacking out on his bedroll with his boots on, he took them off, along with his damp socks, and set them inside his tent to dry.

A sergeant from one of the other regiments noticed this as he was passing by.

“You got good training, Private,” he said, coming over and sitting down with a grunt. (He sported a bit of a paunch and stubble that may have been gray.) “The last thing you need is your feet rotting out from under you.” He rolled a cigarette and looked over at Landon. “First battle?” he asked gruffly.

“Nope.”

“Still nervous though, eh?”

Landon nodded ruefully.

“I am too,” the sergeant said then snorted. “And I’m one o’ them battle-hardened soldiers, or so they say. No shame in being nervous, son. Just remember your training and keep your head about ya.”

Landon found he could only nod again.

The sergeant offered him the cigarette he had just rolled, and Landon took it, even though he didn’t smoke much. The older man rolled another one for himself and they smoked quietly (except for Landon’s occasional coughing) for a few minutes. At last the Sergeant flicked his cigarette stub into the mud and stood up with another grunt.

“Take care of yourself,” he said and they shook hands.

“You too, Sarge.”

It was the older man’s turn to nod. He gave a tight smile, then turned and headed back to his regiment. Landon never saw him again or found out what his fate was. He hadn’t even learned his name.

September 18th, 1863

Ward in the Carver General Hospital, Washington, D.C. Photo: National Archives

The battle was worse than anything Landon had ever seen. They were fighting in dense woods, and there was more of everything: smoke, screams, blood, gunfire… and a cacophony of noise. The only thing Landon could hear over it was the sound of his own heart pounding. But he remembered his training, like the sergeant had said, and threw himself into the battle. He stayed focused, even when bullets whistled past.

He fired again and again, and part of his mind recoiled when he saw bodies falling, knowing that he probably had shot at least one of them.

Landon ran forward, and then was stopped by a burning, blinding pain in his right foot. It felt like it was on fire. He looked down, horrified, and saw a mess of blood and shredded boot leather at the end of his right leg. He screamed and dropped to his knees, and the last thing he remembered was being dragged from the battledfield.

May 26th, 1864

Landon wouldn’t see combat again. His foot was too badly injured to be in the infantry, but it was still there, for which he was thankful. It was dreadfully sore most of the time, but when he saw all the veterans with missing limbs, he felt it wouldn’t be right to complain.

After being released from the hospital, Landon had been transferred to the Veteran’s Corps and was now stationed in Washington D.C. He could still handle a rifle and stand and march (although haltingly and with a limp), so he was allowed duties like standing guard. And that was what he was doing this particular day, at none other than the White House!

North Front of the White House at the time of Lincoln's inauguration. Photo: Library of Congress

It was humid and the sky looked like a storm was on the way, and sure enough, it wasn’t long before a mighty cloudburst came and drenched everything. He tried not to let the awful pain in his foot distract him–he was determined to stand his watch faithfully, so he kept an eye out for anything amiss, which was hard to do through the sheet of heavy rain. He did see, however, that someone had come onto the porch and was waving him over urgently. He was loathe to leave his post but also worried that something might be seriously wrong. Given that this was the White House, he decided it was better to find out what was going on and hurried over, trying not to limp. It didn’t take long for him to see it was President Lincoln beckoning him.

He got to the porch as quickly as he could and saluted.

“Come stand on the porch until the rain lets up,” Lincoln told him. His voice had a noticeable southern twang. Kentucky maybe?

“Sorry, sir, I have orders to stay at my post,” Landon replied.

“Lincoln’s giving the orders here,” came the sharp reply.

Landon saluted again and said “yes sir!”

He stepped onto the porch and appreciated the relief from being pelted by the driving rain. The President came to stand beside him, and Landon saw that the descriptions of his great height were not exaggerated. Lincoln asked his name and unit and where he’d gotten the limp. Landon told him his story, and Lincoln listened carefully, hands crossed behind his back and head bowed. Landon finished and the president simply stood solemnly, not saying a word.

Presently, he looked up into the distance. When he spoke, his voice was what Landon thought of as reverent.

“Thank you for your brave service,” he said and offered a handshake.

It was something Landon hadn’t dared to hope for. He was dazed, and there was a roaring in his ears, but he didn’t hesitate to accept the handshake.

Then he wasn’t sure what to do or say. But Lincoln soon brightened and asked, “By chance are you partial to jokes?”

“Why, yessiree! I sure do,” Landon replied, whereupon Lincoln shared one about a man and his pet donkey in a bar. Landon laughed and slapped his thigh then told one of his own. Lincoln laughed too, so for the next several minutes, they swapped jokes on the porch of the White House.

Soon the rain started to let up, and Lincoln excused himself, saying that he had business to attend to.

“It was a pleasure to meet you, Private Baird,” he said and once again offered an eagerly taken handshake.

“It was my honor, sir!”

Lincoln patted his shoulder and went back inside the White House.

This was Landon’s most cherished memory, one he was extremely proud of. He vowed then and there that he’d take every opportunity to tell the story. And he did.

April 14th-15th, 1865

Landon was off duty when his friend, Jack Miles, burst into the barracks and told everyone the president had been shot. There was a manhunt underway to catch the assassin, but everything was in confusion. Rumors were swirling about a conspiracy to murder not only the president but also other government leaders.

As fate would have it, though, the only success the conspirators had was with President Lincoln, who died early the next morning, April 15th, 1865.

The outpouring of shock and grief and anger was palpable everywhere. And Landon was in the thick of it. He both fed it and was swept along by it. Somewhere, in all the turmoil, though, he remembered that it wasn’t even a year ago that he’d met Lincoln.

This damned war is all but over! He deserved so much better! Landon thought, his rage subsiding, replaced by a profound sense of loss.

April 15th-21st, 1865

VRC regulation sky blue uniforms (Sergeant Robert Black and Private Herman Beckman of Company F, 8th Veteran Reserve Corps); photo: The Library of Congress, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

Landon, as part of the Veterans Corps, joined Lincoln’s funeral procession in Washington D.C., following the president to where he would lay in state in the Capitol Rotunda until April 21st.

Bells were tolling, minute-guns were firing, and all around were faces that expressed the same anguish Landon felt. When the procession reached its destination, he felt an emotional stab that brought tears to his eyes–he had been here just last month to watch the president’s second inauguration.

What happens now? he wondered. He had heard people say that Andrew Johnson, who was now president, was a drunkard. Could he hold the country together? Had everything they fought for been pointless?

That night, Landon wrote home, finally able to tell about what he’d experienced in the last few days. He encouraged his family to make the trip to Columbus, where the funeral train would be stopping on its way to Illinois. He finished the letter and, with a sigh, set it aside to mail the next day.

June 26th, 1865

Mary Surrat. Photo: Mathew Benjamin Brady - U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18731589

Landon’s friend Jack was also one of Mary Surratt’s guards. Not that any guards were needed. She was in a poorly way, so much so that she’d been excused from attending the last few days of her trial.

Jack came to the entrance of the hall where Surratt’s cell was and waved Landon over. It was time for him to take the next shift of guard duty, but there was clearly something urgent, and Landon guessed what it was.

“The verdict’s back?” he asked quietly.

Jack nodded and whispered as well. “Guilty. They’re gonna hang her. But it’s not public yet, so keep it under your hat.”

“Mum’s the word,” Landon acknowledged and looked back at Suratt’s cell. He couldn’t help but pity her, she was so wretched. At the same time, if she was part of the conspiracy to assassinate President Lincoln, she deserved what she got.

He sighed. “You gonna tell her?”

Jack shook his head emphatically but continued whispering. “Good God, no. There are orders that she can’t be told until the day before.”

I guess that makes sense, Landon thought.

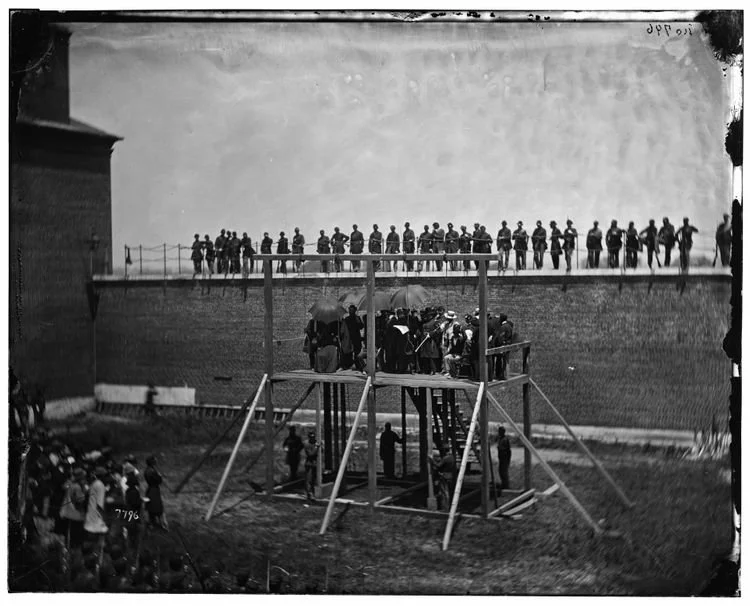

July 7, 1865

Landon had gotten his honorable discharge a little over a week ago but still was given a ticket to attend the executions. (He wasn’t sure why–maybe because he’d been one of Mary Surratt’s guards.) He was told, however, that fewer than 200 such tickets were issued, so he should feel honored. Privately, he considered it more of a duty than an honor, but he kept that to himself and was there with his ticket right on time.

He was sweating copiously. It was hot and felt like it was getting hotter by the minute, but he strongly suspected that wasn’t the main reason for his sweat as he watched the four prisoners being led out: Lewis Powell, David Herold, George Atzerodt, and of course, Mary Surratt. It was only afterwards that he found out how profusely she’d wept and wailed when she was told she would be hanged. He was glad his discharge came through in time so that hadn’t been there.

Gen. John F. Hartranft Reads Warrant Reading the Death Warrant, July 7, 1865. Courtesy Library of Congress

It was no surprise that Mary had to be helped across the courtyard then up the steps of the scaffold. When all the prisoners were there, they were forced into chairs. Mary was on the far right.

A nearby soldier nudged him and said, “Hey, Surratt’s got the seat of honor!”

Landon’s eyebrows shot up in disgust, but he didn’t respond. He hadn’t known the far right chair was the “seat of honor” in a group execution. It was still crude, he thought.

For Pete’s sake, they’re gonna be hanged. Show a little decency.

The four were attended by clergy, then had their arms and legs bound with white cloth. The execution order was read, the nooses were tightened around their necks, and white bags were put over their heads. They were helped to stand, and about ten seconds later, dropped to their deaths. It looked to Landon like Surratt died immediately. He supposed he was glad for that and was satisfied justice had been done.

July11, 1865

After the executions, Landon wanted to get out of Washington as soon as he could. He sat on a bench on the bank of the Potomac and brushed his fingers over his train ticket. This is probably the last time I’ll see this place, he thought and wondered whether he regretted that.

He was still in his uniform. He hadn’t had enough money for both the ticket home and civilian clothes, so he’d taken out his housewife (maybe for the last time), stitched up his uniform, and washed it as best he could. He guessed Liam and George were doing the same. They would soon get their own honorable discharges, and then they’d all be reunited back at the family farm in Ohio. He marveled at their extraordinary luck. Liam had been wounded, but not maimed, and George had gotten away with only minor injuries. The main thing was that all three had survived and were in one piece! If Landon believed in miracles (and he wasn’t sure he did) that’s what he’d call it.

He was anxious to see his whole family, but especially those two. He wasn’t the same man he’d been when he’d enlisted three years ago. He’d seen too much. Done too much. Surely it was the same with them? He wondered if they asked themselves the same question that kept nagging at him: Can I put all this behind me?

I just don’t know, he admitted to himself. But come hell or high water, I’m sure gonna try!

And the first part of that was going home. His small bag was beside him, packed with his few belongings. He’d written to his family to let them know when his train would get in, so they’d be there to meet him. (Ma and Pa were beside themselves with delighted relief.) He wasn’t going to stay too long, though. He was just 21–there was too much to see and do…

The End (for now)

Map showing Athens, OH (top, center), Landon’s home; Chickamauga, GA (bottom), where he was wounded at the Battle of Chickamauga in 1863; and Washington DC (right), where he finished out his service.