The Restless Soul

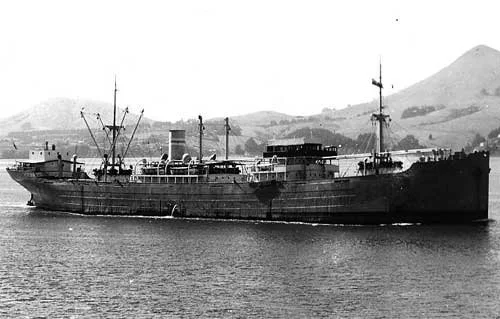

MS Gausdal; photo: warsailors.com

Walter Dubois never knew Nils Nilsen, captain of the MS Gausdal, a Norwegian freighter en route from Venezuela to Cuba. The two did cross paths, however. It was on the morning of June 26th, 1949. The weather was clear with a warm breeze, so Captain Nilsen ordered the hatch coamings to be opened to air out the lower decks. His mood mirrored the weather right up until an agitated crewman informed him he was urgently needed in the hold. He went immediately, of course, and that was when he encountered Walter, or rather, Walter’s body.

Oddly, the only thing found on him was his identification certificate--no money or any other belongings. And after a brief examination, Captain Nilsen concluded that Walter had died from a fractured skull, which raised some questions: Was he robbed and murdered? Or did he fall while trying to stow away? These questions were never answered. After a cursory investigation, Walter was buried at sea. But as you’ll learn, there was much more to Walter’s life than his mysterious, and rather tragic, end.

***

We begin with an ad in the May 8th, 1920 edition of The Caller, the local newspaper of Corpus Christi, Texas: It read:

When you need a cold drink come to the

Uneeda Cold Drink Stand

417 Mesquite St.

(Walter M. DuBois, proprietor)

Now you have to understand just how proud of this ad Walter was. First of all, there was the spelling: You Need A as one word, U-N-E-E-D-A. His mother, Liliana, had objected at first, but he’d talked her into it. Which made him quite pleased with himself, although he hadn’t considered that she was just humoring him as doting mothers sometimes do (especially with their only child). The other thing he was proud of was how impressive it was to be the proprietor of anything at nine years old–okay, almost ten, which Walter was quick to tell anyone who asked his age.

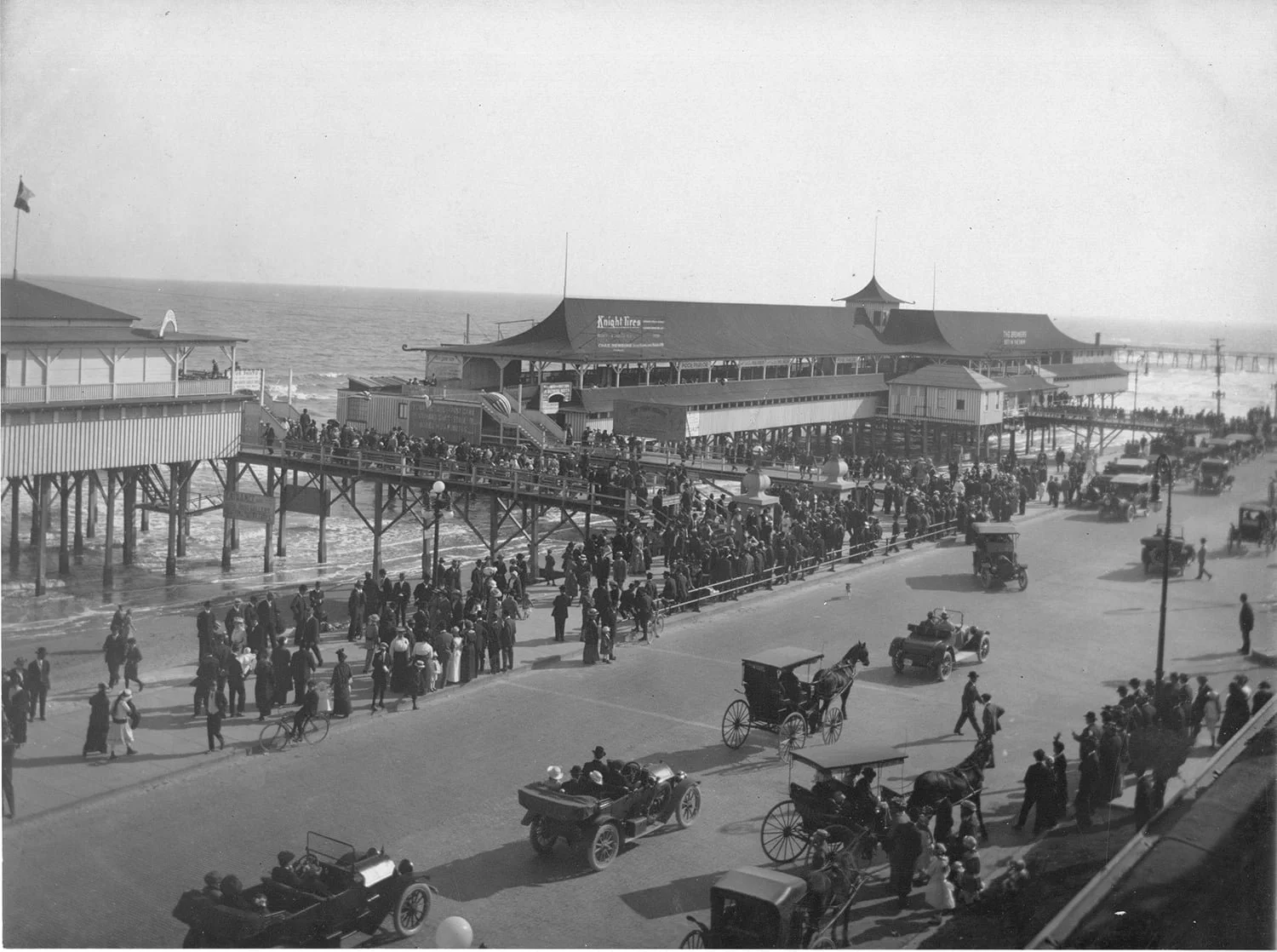

Mesquite Street on September 14, 1919, following the hurricane; photo: Corpus Christi Caller Times

He was sitting in his stand, when he heard a car coming down the road. It was Uncle Al’s Model T. He and Walter’s father, Aaron, were helping out with the rebuilding after a hurricane had hit Corpus Christi the previous fall. They were taking a dinner break, and Walter waved as they pulled into the driveway.

“Hola, Papi, Tio Al!”

Practicing Spanish with Mother was one of the three good things (as far as he was concerned) that had come out of having to stay at home during the flu outbreak. (The papers had called it a pandemic, but Walter didn’t really care. He was just glad it was pretty much over.) Mother said that being able to speak Spanish honored her father, his Grandad Ramon, who’d emigrated from Spain almost fifty years ago.

“Your booth looks really nice,” said Uncle Al.

Walter grinned. “Daddy helped me build it.”

The second good thing about the pandemic was that he’d gotten to help out in Daddy’s workshop.

The front door opened and Mother came out. She gave Daddy a kiss, hugged her brother, and then turned to Walter. “Don’t you have something you want to ask your uncle?”

Walter hesitated. The third good thing about the flu outbreak was that Mother had taught him all about writing. She was delighted that he was good at it, which delighted him, but it also made him desperate not to disappoint her.

Walter saw Mother give Daddy a look.

“Well, go on,” Daddy said and gave him a nudge. “Dinner’s on the table.”

Walter was a bit indignant at being prompted, but knew better than to show it, so he spoke up. “The paper’s having an essay contest for this Liberty Loan thing in July...”

Uncle Al nodded.

“And I was thinkin’ I might write something about the army, but I don’t know much about it. Could I interview you?” Mother had told him to put it just like that, an interview.

A troubled look flashed across Alvaro’s face. He’d gotten back from the Great War more than a year ago, but memories of the trenches and the fighting still haunted him. Walter started to worry the answer would be no, then Uncle Al’s troubled look faded.

“Sure,” he said. “I’d be happy to do that.”

Walter was relieved and elated, but that soon ended as he realized everything he’d have to do over the next few weeks.

His father nudged him again. “Well, what do you say? Go on, time’s a wastin’ young ‘un.”

Walter was sheepish. “Oh, sorry. Gracias, Tio Al!”

***

Walter never thought his essay, “The Benefits of Enlistment in the Army,” would win any prizes. But it did–first prize, in fact, which still amazed him. The best part, though, was that Mother and Daddy (and Uncle Al and Aunt Minnie) were proud of him. Although he had to admit, the $75 prize money was pretty nice too. (By the way, $75 dollars in 1920, would be more than $1,400 in 2025.)

State Senator Harry Hertzberg. Image: By Texas Legislators - http://www.lrl.state.tx.us/mobile/memberDisplay.cfm?memberID=2433, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=65345190

And now, he was about to read his essay in San Antonio. It was exciting, but nerve wracking too. And the auditorium was hot and stuffy, so he was sweaty on top of everything else. Before he knew it, though, Senator Hertzberg, who’d recruited him to do the presentation, finished his speech with: “So y’all remember to sign up for a Liberty Loan to keep our great country free!”

Then he turned to Walter and beckoned. “And now, let’s give a warm San Antone welcome to the youngest orator in America, Walter DuBois!”

Walter was nervous as he made his way to the podium. Senator Hertzberg lowered the mic, and Walter stepped up. He found, however, to his utter terror, that he couldn’t remember a single word of his speech. He breathed a sigh of relief, though, when he patted the nifty pocket inside his suit coat and felt the copy he’d put there. (He’d been a bit miffed when Mother had insisted he do so, but now he was very glad she had.) He took it out, unfolded it, and looked out at the audience. There, in the front row, were his parents. Mother smiled and Daddy winked and gave him a thumbs up. And with that, he began speaking.

***

The next eight years flew by with Walter doing all of the normal growing up things, so let’s fast forward to his high school graduation party. He appreciated all the work Mother had done to throw the party, but early on, he whispered to Uncle Al that they needed to talk privately.

They snuck out to the front porch where Uncle Al lit a cigarette.

“Now do I understand correctly that you got a job offer from Gulf Oil, but you want to join the army instead?” He asked, taking a drag.

Walter, who’d started smoking not too long ago, borrowed the matches and lit up as well. “Yessir,” he replied, coughing and blowing smoke from the corner of his mouth.

Alvaro hesitated. He looked like he was fighting some internal battle but said at last: “Take the job with Gulf. It’s in Galveston?”

Walter nodded, surprised and dismayed. He’d thought his uncle would be pleased about him joining the army.

Uncle Al fought another brief internal battle, then went on. “Your dad is sick. He and your mother didn’t want you to know, but I think you should.”

A cold shiver went down Walter’s spine. “Dammit, I shoulda known,” he said clapping a hand on the porch railing. “He’s been havin’ trouble gettin’ around…”

Uncle Al put hand on his shoulder. “They hid it from me too. Don’t kick yourself.” He paused and took another drag. “Anyway, they don’t need to worry about you being in the army, and Galveston is likely closer than wherever the army would send you.”

His tone turned sharp. “And don’t you dare breathe a word of this. Lilly would have my head on a platter if she knew.”

Walter had to agree. Mother’s temper was not to be trifled with.

He paused to let things settle a bit. It was one of those situations where all sorts of feelings and thoughts jumbled against each other. “Do you know what’s wrong?” he asked at last.

Alvaro shook his head. “Not for sure. Sounds like it may be his heart.”

Worry and guilt were at the forefront of Walter’s mind: He still wanted to join the army, no two ways about that, but if the best way to help his folks was to take the job in Galveston, that’s what he’d do.

And so, in August of 1928, Walter started a job as bookkeeper in the Galveston, Texas office of Gulf Oil.

***

Galveston in the late 1920s; photo: Galveston Historical Society

Another thing you need to know is that Galveston’s nickname at that time was, “Sin City of the Gulf.” And Walter learned quickly that it hit the nail right on the head.

He took a swig of gin and leaned unsteadily against the makeshift bar of his favorite speakeasy. Dad and Uncle Al had warned him about what he’d find in Galveston, and sure enough, they were right. All of the not-so-wholesome opportunities had been a shock… at first. But in the year and a half he’d lived there, Walter’d taken a liking to gambling, even though it’d made for some troublesome debts. And in the same spirit, he’d sampled the offerings at various bordellos and found that they were also to his liking. But tonight, it was just him and a few pals getting drunk.

Afterwards, Walter staggered back to his room at the boarding house and dropped into bed. He was dead to the world until the telephone in the hall rang early the next morning. He winced and groaned and put his pillow over his head, but going back to sleep was not to be. Shortly, there was an equally wince-inducing knock. He got out of bed, noticing he was still in his clothes from last night, and lurched to the door. It was Jake, who rented the room across from him.

“You got a call.”

It was Uncle Al. Dad had died early that morning. The shock brought Walter fully awake. It was far worse than he’d imagined.

“How’s Mother?” he asked.

“About as good as can be expected.”

“Give her my love.” He struggled for words. It felt like he’d been kicked in the stomach, but took a deep breath. “Tell her I’ll be home just as soon as I can.”

“I will. Take care, sobrino.”

“You too. I’ll see y’all soon,” he said and hung up.

Back in his room, he sat on his bed, reeling with a profound sense of loss. He allowed himself some tears. And when they finally stopped, he got cleaned up and went to get a bus ticket home.

***

As you’re probably well aware, funerals are almost always sad, somber affairs, and so it was with the funeral for Aaron DuBois. It was hard for everyone, but I’m sure you also understand it was hardest on Walter’s mother. As a dutiful, loving son, Walter did his best to console her, but it was weeks before she started to get back to normal, and even then, Walter soon realized that “normal” would never be what it had been before Dad died.

He stayed on in Corpus Christi to help out, but that was only partly to support Mother. After the stock market crash last fall, he’d figured his job would be on the chopping block. And sure enough, the axe had fallen. He didn’t say anything about it to Mother, though–she didn’t need any more on her mind.

Little did he know, however, he wasn’t fooling anyone…

“How’s your class going?” Mother asked as they ate dinner after church one Sunday afternoon.

“Pretty good,” Walter said. “You know, I never thought of myself as a teacher, but there it is.” He smiled at her. “And it lets me use all the Spanish you taught me.”

She smiled in return, and they ate in companionable silence for a while.

“I appreciate your staying on to help out after Daddy died,” she said and put down her fork. “But if you’re not going back to Galveston, you need to find something steady here.”

He looked away, clearly ashamed, so she took his hand.

“Now don’t you go feelin’ guilty ‘bout losing your job. It’s nothing you did. This Depression is putting lots of people out of work.”

Walter wasn’t sure he agreed, but was definitely sure that he never should’ve tried to fool her.

“I get a feeling you have something in mind,” he said and was glad to see an old familiar glint in her eyes.

“Just so happens I do. There’s an open spot on the police force, and Mayor Shaffer owes you a favor for those speeches you wrote for his campaign.”

She gave him a sidelong glance. “I could maybe put in a good word too.”

Walter laughed and wondered, not for the first time, just how many connections Mother had in city hall.

“What’ve I always told you?” she asked.

“That it’s good to have friends in high places.”

She nodded. “Yes, indeed. Especially when they owe you favors.”

***

Illustration of Walter DuBois by Charlotte Easterling

Walter, as you might’ve guessed, got the job on the police force, and in less than a year was promoted to detective, which, as it turns out, may have been a bit hasty…

For the first few months, he’d mainly handled thefts and possession busts, but then came his first missing persons case, which ended grimly. He showed up at the scene, a train yard, and tossed his jacket in the back of his car. (Detectives were supposed to wear jackets and ties on duty, but given the sweltering heat of late summer, shirtsleeves would have to do.) He flashed his badge to a uniformed cop keeping a small crowd behind a cordon, and hurried over to another detective near a train car surrounded by firemen.

He recoiled at the strong smell of gasoline and covered his nose.

“Is it the kid, Murph?”

The other detective, older and more grizzled, replied with a grim nod. They watched as two firemen in gas masks lifted a small, still body through the hatch in the top of the tank car. It was a local boy named Billy Smith who’d been reported missing yesterday and had been found just an hour ago.

“Good god,” Walter whispered. “Are we sure it’s an accident?”

Murph nodded again. “Not a sign of anything suspicious.”

Even so, Walter dreaded the thought of writing the report. He tried to focus on the details he’d need to include, but couldn’t take his eyes off that kid’s body being taken away. Then, he realized the next thing he’d have to do would be to pay a visit to Billy’s folks. That thought made his dread even worse, although he hadn’t thought that was possible. The only thing that helped was knowing Murph would be with him.

He spoke to a reporter from The Caller, then looked at Murph and sighed. “I guess we’d better get going.”

Talking to the boy’s parents was just as bad as he’d feared. He felt for them, but there was nothing he could do but tell them Billy hadn’t suffered. (He suspected that was a lie, but it was one he could live with.) He and Murph offered condolences.

Yeah, Walter thought, Lotta good that’ll do…

Afterwards, they quite understandably needed to unwind and headed to a speakeasy typically dominated by cops. Walter immediately slugged back a gin and liked the way it burned going down. It took a bit of the edge off, but the image of that kid, and his folks, kept intruding.

Murph refilled his glass and put a hand on his shoulder. “Today was tough. They’re not usually that bad.”

Walter nodded. He liked being a cop, and he was good at it. But today had shaken him.

One more will smooth things out, he thought and knocked back another gin.

***

Next, we’ll jump ahead to a hot, muggy day in May of 1935. The courthouse where Walter was in a hearing might have had air conditioning. But even if it had, he still would’ve been sweating, as he sat in the witness chair being questioned by the DA.

“I did not hit Chief Mace over the head, as alleged,” Walter said indignantly. “I hit him between the eyes with my fist!”

His lawyer, B. D. Rappaport, one of the most celebrated (and expensive) lawyers in the county, cradled his forehead in his hand. He looked to be in great pain. On the other hand, the DA, Daniel Forsythe, looked immensely pleased.

“I have nothing more, your honor,” he said with a self-satisfied smile.

Judge Westervelt managed to keep a straight face.

“Do you have any questions, Mr. Rappaport?” he asked.

And Mr. Rappaport most certainly did. As he and Walter had discussed, he asked about the events the previous December, just a week after Prohibition ended, when Walter had fired his gun in a bar. Walter said he wasn’t there to cause trouble for anyone–he just needed to track down someone accused of assault.

“So, you were just doing your job. Is that correct?” Rappaport asked.

“Yes, sir,” Walter replied.

“Did you have anything to drink before you fired your gun?”

“Well… yes,” Walter said. “But I wasn’t drunk.”

Rappaport nodded. “And Chief Mace accused you of being drunk on duty? And that’s why you hit him?”

“Yes, sir! He’s always had some grudge against me, ever since I made detective!”

Rappaport gave him a subtle gesture to settle down. “And that’s why you got arrested and fired?”

“Yes, sir,” Walter said, doing his best not to sound resentful.

Rappaport proceeded to admit that Walter had a problem with alcohol, but that his record on the police force (before the bar incident and slugging the chief) was sterling. He followed up with Walter’s other good activities, such as teaching a Spanish class, participating in church fundraisers, and supporting his mother.

“And in conclusion, your honor, he has character references from Mayor William Shaffer and retired State Senator Harry Hertzberg.”

Judge Westervelt looked thoughtful. “Seems like we may have a situation where we can settle this matter without going any further. Do you gentlemen agree?”

Rappaport did. Forsythe, however, looked unhappy, but after a few seconds he nodded reluctantly.

“Looks like you may have a suggestion, Mr. Rappaport,” the judge said. “Care to share it with us?”

“Well, your honor,” Rappaport began. “It’s clear that Mr. DuBois getting fired from the police force has to stand.”

There was unanimous agreement on that point.

“But my suggestion is to drop the charges and send him to a sanitarium for rehabilitation from alcoholism. That way, he can get sober and continue to do good things for the community.”

Forsythe appeared to be weighing his options, but it didn’t take long for him to realize what would be best for his career. Still, he looked like he had a bad taste in his mouth when he said, “Agreed, your honor.”

Judge Westervelt banged his gavel. “So ordered. The charges in this case are dropped. Mr. DuBois, you will report to the Moody Sanitarium in San Antone as soon as arrangements can be made. And best of luck to you, young man.”

***

Ad for Moody Sanitarium; photo: Texas State Historical Association

Anyone who’s been in the hospital for an extended time can sympathize with Walter’s feelings about his time in the sanitarium. And although he was glad not to have to go to trial, and maybe jail, by the time he got out, he doubted whether he’d really gotten off so easy–aversion therapy had been hell. But it had worked. (Even a faint whiff of alcohol would make him sick to his stomach.) So he’d been grateful to get out of the sanitarium and back to Corpus Christi where he could start rebuilding his life.

Now let’s jump ahead to 1939, which also marked a little over 5 years of sobriety and holding down a job.

“Smells great!” he said as he walked into Mother’s kitchen. It wasn’t the one he remembered from childhood, but he’d gotten used to it. There was a glazed cinnamon cake on the counter and he opened the oven where a dish of enchiladas bubbled.

“Mmmm, my favorite.”

“Well, of course,” said Mother giving his arm a squeeze. “What else would I fix for my boy’s 29th?”

Walter patted her hand. Mother selling the old house had been hard, but getting to have the foods he’d grown up with softened the blow. Besides, he knew there was no question that she’d move into Robert’s house when they got married.

Walter realized that was three years ago and shook his head in wonder. He’d been ready to resent Robert, but found he just couldn’t bring himself to dislike the man. He was easy to get along with, and had a good sense of humor, but most importantly, he was good to Mother. She seemed happy again, and that was the main thing.

“Penny for your thoughts,” Mother said.

Walter looked up. “Oh, just thinkin’ ‘bout how time flies.”

“Sure does, but you’ve done a good job getting cleaned up and holding down a job.”

Walter’s smile was rueful. Memories of the sanitarium resurfaced, and yes, he was happy to have a steady job, but he was sick and tired of bookkeeping.

“Somethin’ eatin’ at you?” Mother asked.

Walter hesitated. He had an announcement but had intended to make it after supper. As usual, though, Mother was on to him.

“It’s the war, what with the Japanese, and that Hitler…,” he trailed off, then turned to her. “And I feel like grandad would’ve wanted me to go fight Franco.”

Mother shook her head firmly. “No. He left Spain to get the family away from that kind of trouble. He never would’ve wanted you to get involved.”

Walter was only a bit relieved. The larger problem remained.

“Well, I’m glad to hear that, but still, we’re in this war already; sooner or later it’s gonna be official. And I’ll be better off volunteering.”

Mother sighed. “I suppose you’ve talked this over with your uncle?”

“Yes, ma’am, and he agrees with me.”

“I figured that was the case.” She put her arms around him. “I know you wanted to join up a long time ago.”

That coaxed a small laugh from Walter as he thought: Of course you did.

“Have you signed the papers yet?”

“No, but I will soon.”

She didn’t reply, but hugged him tighter.

***

Walter was quite convinced that the Army was determined to keep him in bookkeeping assignments in hot, humid places for his entire enlistment. He’d done boot camp in Texas, which had gone about as well as boot camp can go. Then, thanks in part to knowing Spanish, he was assigned to an ordnance unit in San Juan, as a clerk–a bookkeeper.

Isley Field, Saipan, 1945; photo: USAAF

This led to being stationed at the B-29 base on Saipan (the Mariana Islands… the tropics) in yet another ordnance unit, as–you guessed it–a clerk. Although by that time, he’d come to grips with the fact that the army was nothing if not ironic. Still, it wasn’t all bad. The transfer included a promotion to sergeant, and the General had given his unit a commendation for their support in the Tokyo bombing campaign called Operation Meetinghouse.

He’d just gotten off duty and was hoping no one else was in the barracks tent so he could take a nap in peace. No such luck. Kowalski, a corporal who bunked next to him, gestured at Walter’s cot.

“Ya got mail, sarge.”

“Yeah. Thanks, Ski. I might’ve missed it.”

Walter picked up the letter and saw it was from his cousin, Jimmy Ellington (a Seabee stationed in Hawaii). He finished reading it, and much to his annoyance, Kowalski (who wasn’t blessed with an overabundance of perceptivity) felt the need to follow up.

“Good news?”

Walter rolled his eyes and muttered something clearly uncharitable. Ski just shrugged and went back to his comic book.

Walter left the tent and stopped to take in all the activity. Meetinghouse had ended in March, but that was four months ago, and the bombing runs hadn’t slowed down much. Something big was up, especially since curiosity was being pointedly discouraged. There were rumors about plans to invade Japan, which worried him, but he didn’t think that’d require quite so much hush-hush.

“I guess we’ll find out eventually,” he said to himself and headed to the mess tent for some chow.

As it turned out, eventually was just a couple of weeks. And what was up was indeed big–very big: the A-Bomb. The news said two Japanese cities Walter hadn’t heard of were completely destroyed in enormous explosions of heat and radiation. He didn’t entirely understand, but he didn’t need to. The war was over! No invasion, just V-J Day and then he was headed home!

***

Walter was honorably discharged and by early 1946 found himself back in Corpus Christi. He was glad to have some time to unwind and reconnect with his family and friends, but as fate would have it, his stay didn’t last much more than a year. Job options were limited mostly to much-hated bookkeeping. And despite his protestations, Mother had launched a well-meaning (but ill-fated) attempt to find him a wife. So, when he’d heard that Gulf Oil had opened a supervisor job in Venezuela, he jumped at the chance.

Hot and humid, again, he thought. But at least it’s not bookkeeping!

And thanks to his army experience, a good record with the company, and fluency in Spanish, he got the job even faster than he’d expected. So it wasn’t long before he was waiting to board his plane. He first gave Aunt Minnie a kiss, then shook hands with Robert and Uncle Al.

“Take care,” said Robert. “Give ‘em hell!”

“Yes, sir, I will.”

Uncle Al pulled him into a hug. “Be careful. Don’t get mixed up in anything dangerous.” His voice broke, but he managed, “And be well, too, sobrino.”

A lump in Walter’s throat kept him from replying, so he simply nodded and smiled.

Then it came to Mother. She wept openly and gave him a kiss on the cheek when he embraced her.

“I sure hate to see you go.”

“I’ll be fine. Like I said, I just need a change of scenery.”

Mother nodded. There was nothing more to say. She’d tried to talk him out of it early on, but after several discussions, she’d finally made peace with his decision. “You take care now, hear?”

“Yes, ma’am. You do the same.”

He kept his arm around her until the boarding call came, then he released her and waved as he headed to his plane.

***

Caracas, c. 1949; photo: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection

No one in Venezuela can make a decent glass of tea, Walter thought as he shook his head in disgust and poured sugar into the glass in front of him.

But it was a minor complaint. His job was a definite improvement over his other jobs. And the weather in Caracas wasn’t that different from San Juan and Saipan, so it didn’t bother him too much. What he really liked was the scenery–lots of very old and very new. And his favorite place to sit and watch the comings and goings was a cafe near the seaport. It’d occurred to him that he liked it so much because it reminded him of the port back home. Maybe this is a place I can make life for a while, he thought contentedly.

He sipped his tea, now properly amended, appreciating the coolness in the early evening heat. After a while, he went to wander the docks, avoiding the cargo crews and sailors–they tended to be a rowdy bunch.

Soon, the light was fading. About chow time, he thought and took a shortcut through an alley that led to a diner he liked, and thereby, his meeting with Captain Nilson.

***

Not long after, Robert came down the steps and joined Alvaro in the kitchen. A large cardboard box was open on the table.

“Is she ready?” Alvaro asked.

“Soon,” Robert said. “I’m sure grateful for Minnie’s help. I know Lily is too.”

Alvaro just nodded.

“I was just a friend of the family when Walter’s father died. This seems much harder for her. Stands to reason, I suppose.”

“It is,” Alvaro agreed. “With Aaron, she knew it was coming. She had some time to prepare…”

“And a body to bury,” Robert said.

Alvaro nodded again. “Yes. But it’ll help that there’s a gravestone.”

They continued looking through the box the company had sent. It contained Walter’s possessions: clothes, a few books, some newspapers and magazines and such.

“I wish we could get the police down there to investigate more. It just doesn’t make sense,” said Robert. “You knew him better than I did, but I can’t imagine he would stow away on a ship with just an ID. No money, not even a change of clothes or anything?”

Alvaro shook his head. “I know. Doesn’t make a lick of sense, but they closed the case. Nothing more we can do.”

Robert was hesitant. “Do you think he could’ve been robbed? Killed?”

“Maybe.” Alvaro looked troubled. “We’ll probably never know...” He trailed off when he found Walter’s unfinished letter to his mother. At first, he was unsure whether he should read it but shortly decided to do so. He finished and held his handkerchief to his eyes.

“She should have this,” he said at last, handing the letter to Robert.

“Yes, but after the service.”

They both turned as Lilliana started down the steps with Minnie supporting her. Alvaro went to open the front door, and Robert took her hand at the bottom of the steps.

“You look mighty pretty.”

She managed a wan smile in return and stopped after a few steps. “You know,” she said shakily, “I think he would’ve liked that he was buried at sea. He was always such a restless soul.”

Robert agreed and put his arm around her shoulders as he led her to the car. It was time to say goodbye.

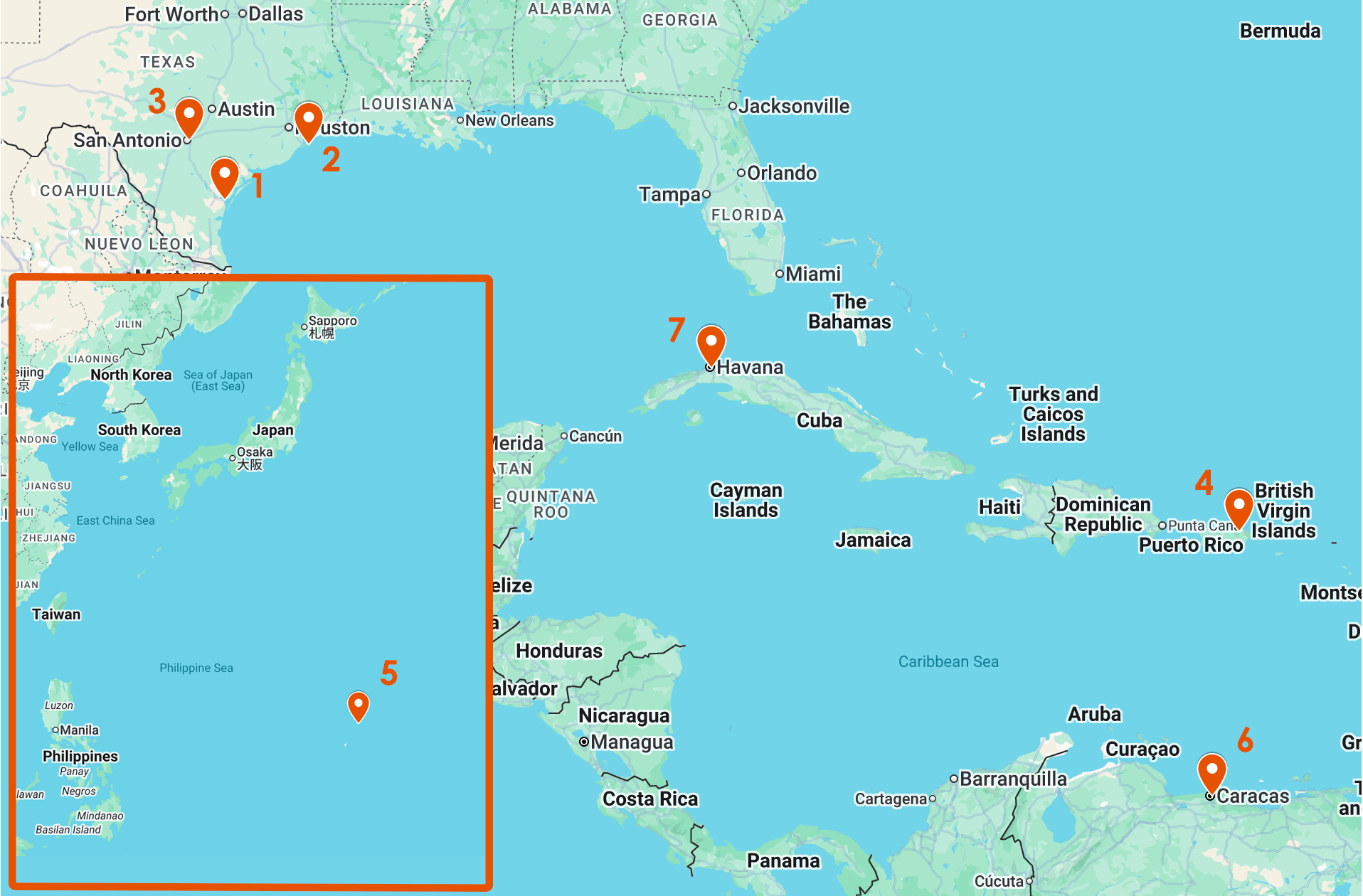

1: Corpus Christi, Texas. 2: Galveston, Texas. 3: San Antonio, Texas (location of the Moody Sanitarium). 4: San Juan, Puerto Rico. 5: Saipan, Mariana Islands. 6: Caracas, Venezuela. 7: Havana, Cuba. The Gausdal was bound for Havana when Walter’s body was disovered. His burial at sea was in the Caribbean.